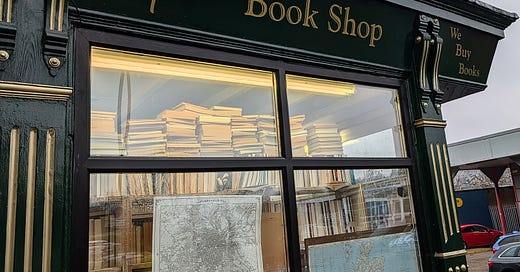

“No one buys books any more, do they? Shame.” So I overheard someone say when I was up in Sheffield a couple of weeks ago — just as I was about to enter Porter Book Shop on Sharrow Vale Road. I hadn’t been there before. I don’t think I browsed for more than forty minutes, but maybe half-a-dozen browsers appeared in that time; some of them even bought books. One prolonged transaction concerned some scarce Stephen Kings (sensibly not kept in the shop itself), with a woman acting as the somewhat daunted intermediary for her son, who was issuing instructions down the phone line. A large sum was mentioned, for two rarities. I left the shop before that bit of business could be concluded.

My own purchases were more straightforward and, to me at least, have some appeal along the lines of what Nicholas Royle calls “inclusions” in books.

Because of those inclusions, as well as the roughly similar condition of these two hardbacks with their weary dust jackets, I’m guessing that what I picked up were copies of two collections by Robert Lowell, For the Union Dead (London: Faber, second impression, 1966) and Day by Day (London: Faber, 1978), that had belonged to the same dedicated poetry reader (though only in the former volume had the owner inscribed his name on the front free endpaper). The inclusions, I found, constitute a small anthology’s worth of newspaper clippings, mostly to do with Lowell and his work.

Among the inclusions here are a couple of outliers. An advertisement for the National Theatre at the Old Vic dates, I guess, from 1973, when Measure for Measure was playing (no Lowell involved, at least explicitly). Copied out separately, meanwhile, in a neat hand, are a couple of stanzas of Stephen Spender: “Not to you I sighed. No, not a word. / We climbed together . . .”.

But otherwise, on paper of varying degrees of yellowishness, these inclusions offer evidence of a critical interest in Lowell sustained (or at least intermittently revived) over many decades. Here is Al Alvarez’s interview with Lowell (“a tall, stooping man of great sensitivity, tact and an almost saint-like gentleness”), published in the Observer in 1963. Also For the Union Dead reviewed by Cyril Connolly in the Sunday Times (“there are many references to a drinking problem”). Further critical responses follow, from fellows as wise as John Bayley, Donald Davie and D. J. Enright. Only Eavan Boland and Fiona MacCarthy are present to counterbalance the blokeishness. In general, the value of Lowell’s verses comes in for some sceptical speculation, alongside the customary measure of praise for technical ability and awe at the darkness he made visible. MacCarthy, reviewing the Life of Lowell by Paul Mariani, Lost Puritan, gets to offer the latest of the retrospective views:

Since his death [in 1977], Lowell’s reputation has plummeted. He-men are out of fashion. The harm he did to others still seems reprehensible. But as Mariani argues, who is not flawed? This long book, often a stream of quotation from Lowell and his entourage, dazzles with the splendour of mid-century American language and technique. Lowell weighed words with precision and zeal, using art to fend off chaos, find salvation.

Whatever revolutions in taste have followed since Lost Puritan was published in 1994, time has stopped down here among the newspaper clippings, with Lowell being both celebrated and put in his place.

The pages of the two collections themselves are unmarked, unannotated. So their owner, if there was just one, has kept his opinions to himself. I looked up the man’s name inscribed in For the Union Dead, and was pleased by the associations it suggested. And all of this reminded me that the last time I’d been in an Oxfam Bookshop I’d overheard a volunteer rather exultantly declare that she removed inclusions (she used a different word) whenever she came across them.

I’m glad these particular Lowells ended up elsewhere.

*

ICYMI: Jon A. Lindseth has donated his estimable Lewis Carroll collection to the author’s college, Christ Church, in Oxford. A truly rare fifteenth-century illuminated manuscript has been discovered in a York convent, “in a shoebox containing leaflets from the 1980s”.

Another mode of “inclusion” is the bookplate. Often one doesn’t have a clue about who the proud plate-owner was but my copy of the first edition of Robert Conquest’s influential poetry anthology New Lines (1956) picked up some years ago in Any Amount of Books has a very grand bookplate of Lord Anthony Quinton which if I knew how to I would happily attach a pic of here. Do they add anything to the value of a book in addition to the interest value?

Always love finding ‘inclusions’ though the one time I was extremely creeped out was a book on Eric Gill at that great bookshop beside York Minster, bunch of seedy clippings on him fell out and i felt sinister for opening the book in the first place. What are the aesthetic rules of removing inclusions? if nice picture clippings I tend to take them out( have one of duncan grant found in old bio of him)