“Hello, possums . . .”

Edna Everage, Melbourne housewife turned Dame and eventually self-proclaimed “Gigastar”, was lucky to have in her entourage one Barry Humphries; he was there from the start, in 1955, until her final appearances on stage and screen six decades later. And he, in turn, was lucky to act as her “entrepreneur” (as she called him): her success meant he could indulge, with Everage-level aplomb, his love of collecting books and art.

On February 13 Christie’s in London is auctioning some of the best of Humphries’s unique collection. Dame Edna’s sequin-spangled dresses and outsize glasses. Paintings Charles Conder. Drawings, designs etc by Aubrey Beardsley, Gustav Klimt, Franz von Stuck and many others. And, of course, books.

Whatever else he was (controversial as well as funny, let’s say), Humphries seems to have been a dedicated collector, in defiance of his early experiences, and eventually became a member of the Roxburghe Club. Geordie Grieg, a friend of his, reported in the Independent his story of being scolded by his mother for buying second-hand books: “Do you have to buy these bits and pieces? You never know where they've been!” Once, returning from school, he found that she had given them all away to the Salvation Army (“you’ve already read them”). Reading a book, not reading a book: what does it matter? Humphries came to own “at least nine copies of his favourite book, South Wind by Norman Douglas”, Grieg noted.

What else is in the collection (but not yet going to auction at Christie’s)? Humphries was the proud owner of Oscar Wilde’s telephone book, “a slim volume as not many of Oscar’s friends had telephones in the last decade of the 19th century” (Evening Standard, 2010). In Munich he bought a book owned by Hitler, and later regretted it, as he told the Sunday Telegraph in 2022. “It has an aura to it that I don’t like. I’m going to try and get rid of it.” Another journalist friend, Ben Macintyre, has him owning choice volumes such as “a first edition of Philip O’Connor’s Memoirs of a Public Baby, an autographed copy of Harold Acton’s Humdrum, the complete works of the poet Wilfred Childe, 19th-century ghost stories and shelves of vintage children’s books”, not to mention what Humphries called erotica “of a superior kind”. Further evidence of such abstruse tastes may be found in a catalogue of books mostly drawn from Humphries’s library recently issued by Paul Rassam:

ARROW, Simon. County Fanny’s Nuptials: being the story of a courtship. Printed for private circulation, and published by G. G. Hope Johnstone, [1907] . . . Though sometimes misattributed to Ronald Firbank, ‘Simon Arrow’ was the pseudonym of the book’s publisher, G. G. Hope Johnstone.

LEE-HAMILTON, Eugene. The Lord of the Dark Red Star: being the story of the supernatural influences in the life of an Italian despot of the thirteenth century. Walter Scott, 1903.

WRIGHT, Austin Tappan. Islandia. New York: Farrar & Rinehart, [1942] . . . Very nice copy in dust jacket, slightly worn at head and tail of spine, in cloth chemise and handsome gilt-lettered and decorated morocco-backed slipcase by Jacques Desmonts . . . A thousand-page utopian novel. ‘Most fantasy novels briefly create a universe, then tell a story in it,’ wrote the novelist and critic, Charles Finch, ‘but Wright’s signal skill, for better or worse, is depth of field, the detailing of his world, so that the novel often reads like Franz Boas by way of Wes Anderson.’

More recently, Humphries’s widow has suggested that the obsession had reached heights comparable to Sir Thomas Phillipps in intensity (if not extent). “I used to say that, with Barry, art and books came first and second”, Lizzie Spender told the Sunday Times. “I tied third with the children. I said it jokingly, but many a true word is spoken in jest.” The books constituted a “secret world”, no possums permitted. “Sometimes he’d leave the kitchen table and say he was going to the library for five minutes, and not reappear for five hours.” “Don’t tell Lizzie!”, he’d implore those who knew of his latest purchases:

She would open a guest room cupboard to discover her husband had erected shelves full of newly acquired books. After they got married Humphries bought the flat below hers for his ever-expanding library and still complained that there was not enough space.

The interview, one of the more engaging items published in the Sunday Times, also notes that part of the business of collecting, for Humphries, was looking after his collection with appropriate bindings etc. “Humphries once commissioned a book cover made of poisonous cane toad skin: the bookbinder had to take a week off sick.”

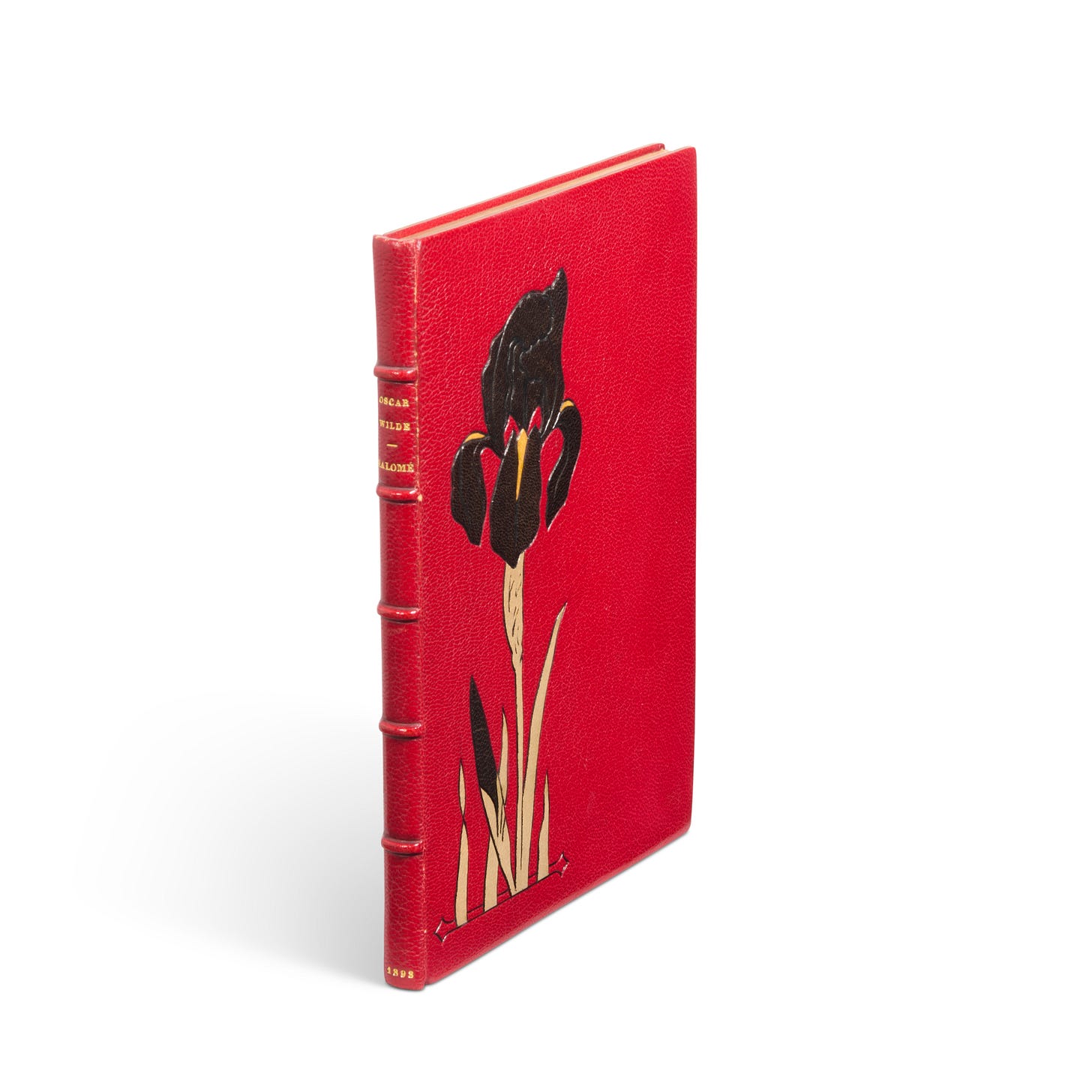

As pictured above, Christie’s is auctioning, among other treasures, an exquisite presentation copy of Salomé (Paris: Paul Schmidt for Librairie de l’Art Independant and London: Elkin Mathews, 1893; estimate £20,000—30,000), inscribed by Oscar Wilde for the writer (and homophobe) Léon Daudet.

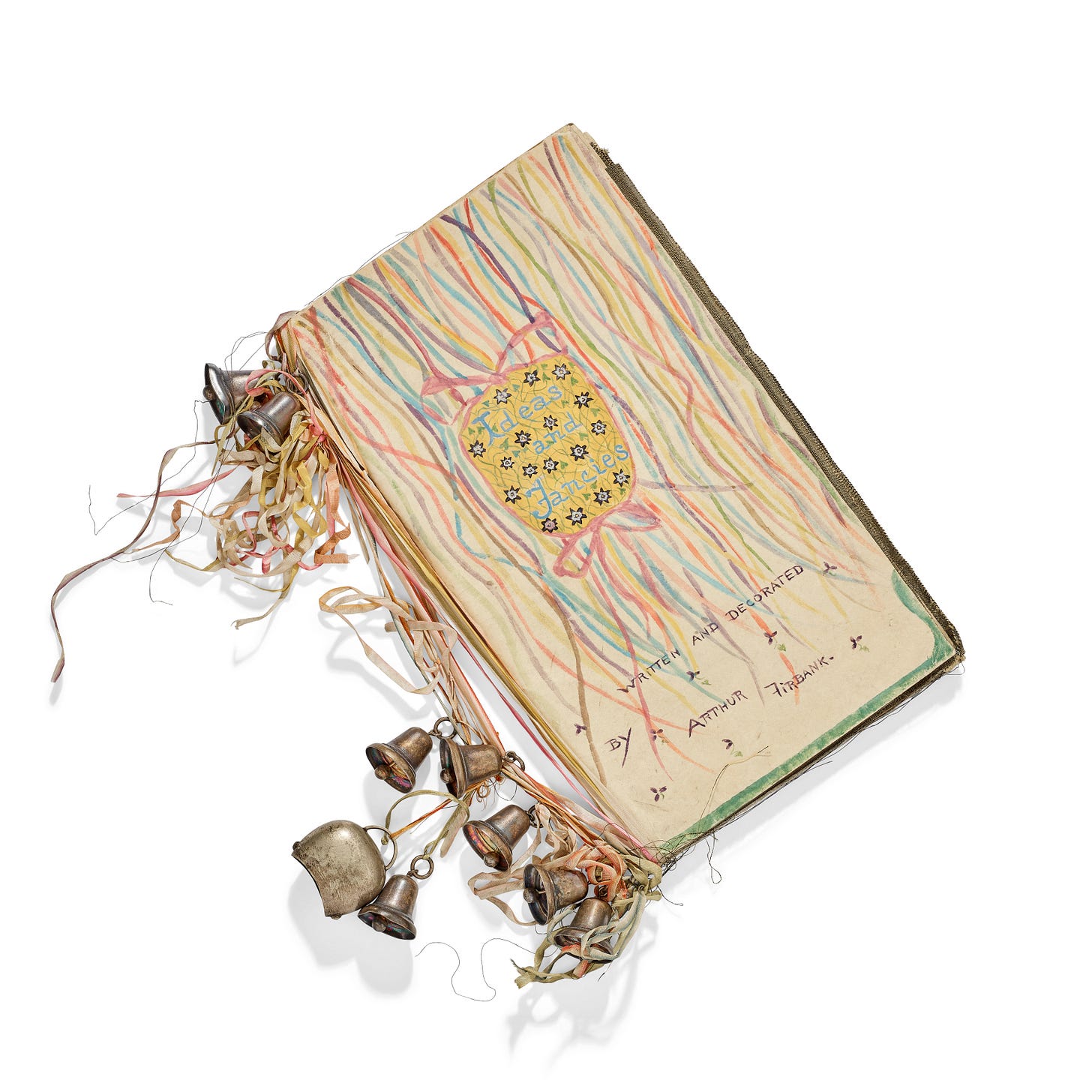

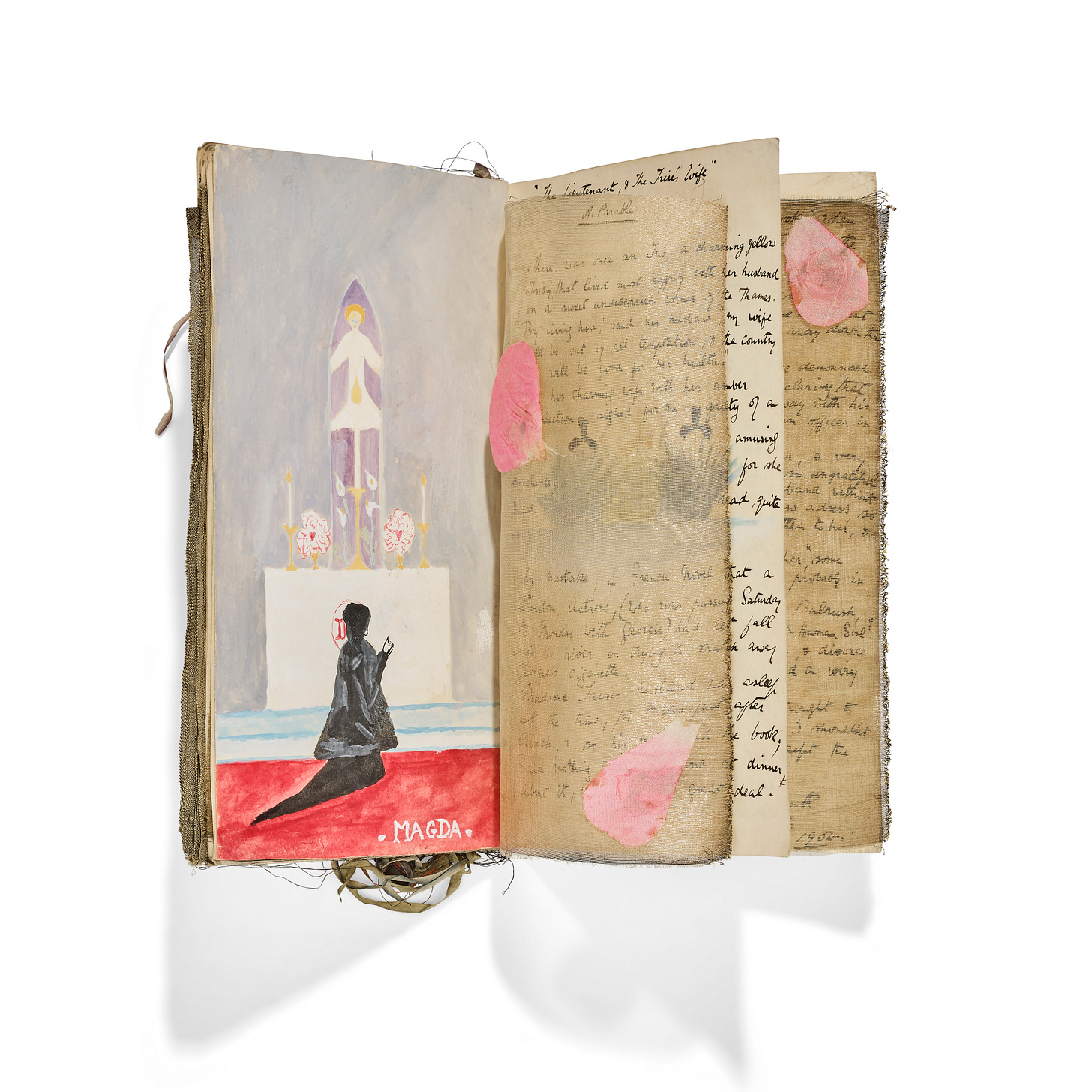

And pictured below? This is the handmade booklet “written and decorated” by the young Ronald Firbank for his mother as a Christmas present in 1904; the outside is decorated with ribbons and bells; the inside contains ten watercolour drawings and two prose fragments (estimate £15,000—20,000).

This is a secret world, now being dispersed, in which I suspect anybody really interested in books might have delighted to lose themselves for five hours rather than five minutes.

*

ICYMI: Barry Humphries wasn’t the only famous entertainer who collected books: see also, for example, Houdini’s magic collection.

Wow, wow, wow - what an absolutely gorgeous collection. I would have loved to tour his home!

Wonderful to see some Baron Corvo in there, someone else with an alter-ego.