Hiding at the back of a biography of Baudelaire: a host of floating Amazon Water Lilies.

Enid Starkie’s Baudelaire, that is – not her first stab at the subject (published by Victor Gollancz in 1933) but her second (published by Faber in 1957). It was published as a Pelican paperback in 1971, not long after Starkie’s death.

Yesterday a friend showed me this very decent copy of the Pelican edition, which he’d picked up at Kenwood House for £3. Nestled among Starkie’s endnotes was this postcard depicting the “great Amazon Water Lily” (Victoria amazonica) at Kew. “The flowers, produced in summer, open in the evening and are at first pure white in colour but fade to pink or purple within 24 hours.” Apt for Baudelaire, I vaguely thought . . . but maybe purely accidental. The postcard implies a well-chosen gift – for Sue, With much love – but assuming the book definitely was the gift in question, who’s to say for sure that Sue didn’t just stick it in the back of the book and forget about it?

Possibly like some fellow idlers who spend too much time in second-hand bookshops and charity shops, I like (and tend to keep in place) the odds and ends that you can find in a book. The book that’s been around the block, let’s say, rather than the pristine artefact (although I fear I like the pristine artefact, too). I’d love to know if other readers/collectors love or hate or couldn’t care less about this form of everyday encounter with repurposed ephemera.

A book historian might say, for one thing, that through such modest additions you can sometimes acquire just a little more information about the book and whoever has handled it, while also being teased with a range of possible further associations. My copy of Cavafy’s poems came with a terrible photo of two blokes larking around in drag, one of them wearing the traditional, comically stuffed bra. A novel by Linda Grant, its spine speaking of an intensive bout of holiday reading, turned out to be richly bookmarked with euro banknotes.

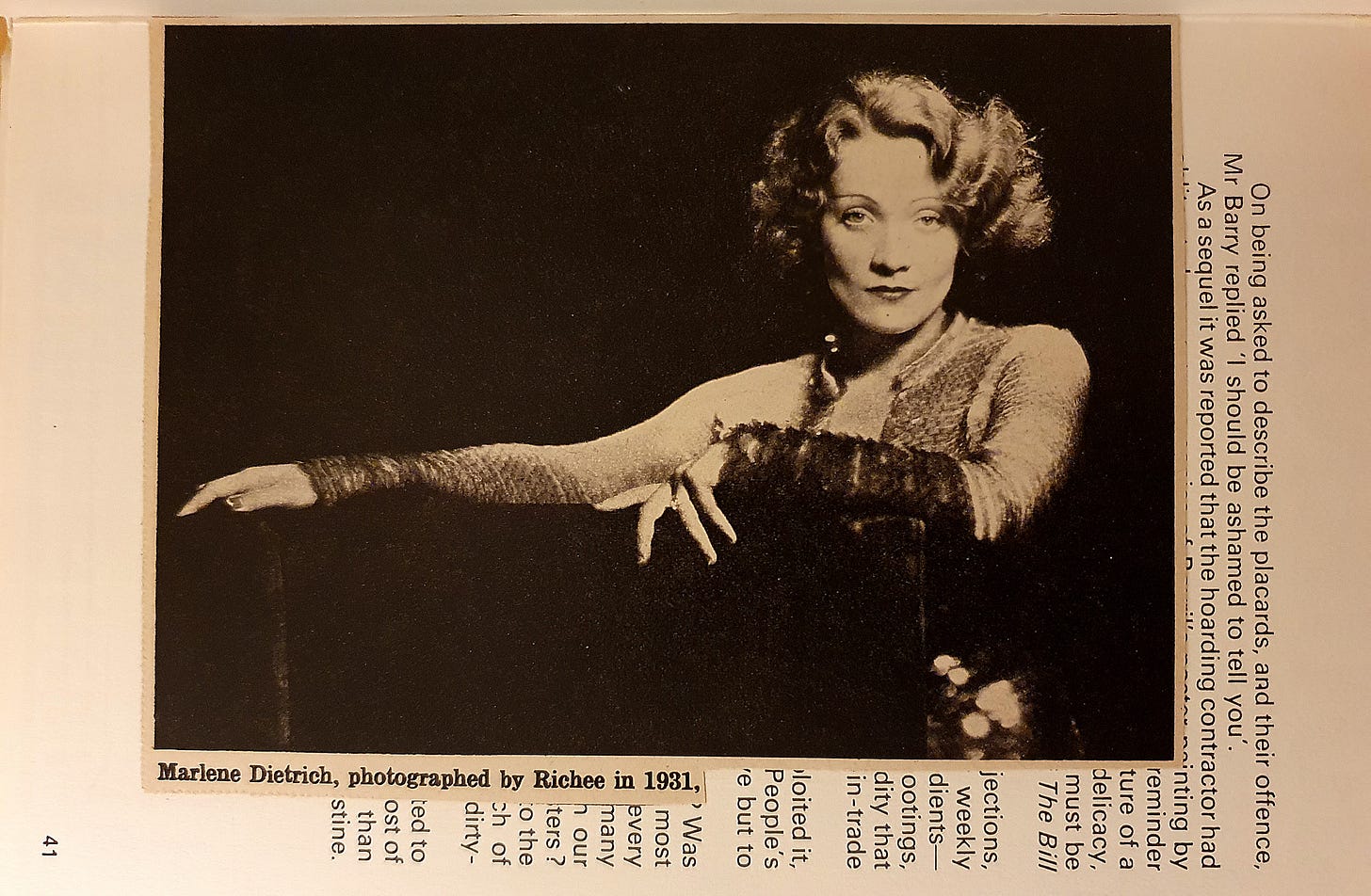

And here is one of two stars of interwar cinema – the other being Carole Lombard – as neatly extracted from a magazine and secreted into the copy of Banned Posters by Maurice Rickards (London: Evelyn, Adams & Mackay, 1969) that I picked up the other day:

Maybe it’s best to separate these suggestive scraps of the past from newspaper cuttings (and the like) that have some direct bearing on the volume into which they’ve been inserted. My copy of the The Ewart Quarto by Gavin Ewart (London: Hutchinson, 1984) comes not only with the poet’s inscription, dated “October 1984”, but a photocopied interview with Philip Larkin, published in the Sunday Times that same month. At the top of the photocopy is a list of names, including Ewart’s daughter Jane and the recipient of this inscribed copy, suggestive of a kind of critical programme of distribution. “I like the three great eccentrics, Betjeman, Ewart and Stevie Smith”, Larkin says in the interview, when asked which modern poets he admires. “They are funny and moving.”

A contrasting purpose seems evident in the cutting that greeted me when I first opened a novel called A Green Tree in Gedde by the Scottish writer Alan Sharp (London: Michael Joseph, 1965). This is also from the Sunday Times, only the cutting comes from a review, the end of a round-up of books, and it has the discouraging tone of a warning sign about steep gradient on the road ahead:

Lastly A Green Tree in Gedde. I’ve placed it last because I liked it least, which is a fair rule in reviewing. . . . A Green Tree in Gedde is over-long and overwritten. The language is showy and inaccurately used. The plot is shapeless and pointless.

The reviewer, John Bowen, goes on to say that he doesn’t care for Sharp’s characters, either. Why stick this in a copy of the novel? Perhaps because Bowen ends by suggesting that Sharp does have “vitality as a writer” and an ability to “communicate an enjoyment of the physical pleasures of life”. The pontifical final judgement is that this young writer needs “our patience”: “Later he may reward it”.

A Green Tree in Gedde is the first part in a trilogy; I wonder if this particular reader of Alan Sharp held out any hope for that possible reward.

In honour of those bibliomaniacs who aren’t yet ready to take a break for mince pies and carol-singing or whatever the season insists on, here’s a brief bout of window-shopping. Mostly on a theme of association copies . . .

Sitwell’s best critic

Edith Sitwell, Five Variations on a Theme (London: Duckworth, 1933), £225

“For darling Helen who was my first and is my best critic with very best love from Edith.” Behind this inscription on the front fly leaf of this first edition, first printing (“slightly bumped” around the spine) lie Edith Sitwell’s feelings of loyal gratitude to her former governess, Helen Rootham. It was Rootham who introduced Sitwell to the French symbolist poets at Renishaw Hall, the Sitwell family seat, in the early 1900s; she had long moved out, to London, when Sitwell inscribed for her this copy of her tenth collection of poems. (Rootham is also the dedicatee of Sitwell’s previous collection, Gold Coast Customs, 1929.) This copy of Five Variations on a Theme apparently comes from the library of the collector and industrialist Samuel Courtauld. And here it is, on eBay.

Anti-Man, Anti-Koontz

Dean Koontz, Anti-Man (New York: Paperback Library, 1970), $500

Back in Time Rare Books has a copy of this scarce early effort by Dean Koontz (or Dean R. Koontz as he appears here). Apparently the prolific novelist later started buying back the rights to early works such as this sensational one about an overpopulated world in a dystopian future to prevent their circulation. But that didn’t stop him signing this copy for a friend and collector of his work, Gary Elswick. “My title”, Koontz explains in this inscription, “was ‘The Mystery of the Flesh’ but the weird crowd in New York were certain that it would be mistaken for a gay novel! So they stuck on this dumb title.”

From Peggy A.

© Shapero Rare Books Ltd

Margaret Atwood, The Edible Woman (Toronto: McLelland and Stewart, 1969), £4,500

This copy of Margaret Atwood’s first novel is accompanied by a letter to the friend, Jerome Hamilton Buckley, to whom the copy is also inscribed (“Peggy atwood”). The future grandee of Canadian literature was then teaching at the University of Alberta. Her letter appears to be mostly concerned with the PhD thesis on “The English Metaphysical Romance” that she never completed; but it closes with a sigh of authorial exasperation: “I doubt that my thesis will turn into a book – I’m developing a phobia about publishers. Are they all as chaotic as McClelland and Stewart, I wonder?” Despite the sigh, Atwood was still publishing with McLelland and Stewart decades later; and Shapero also happens to have a signed copy of her essay collection In Other Worlds, from the same publisher (£125).

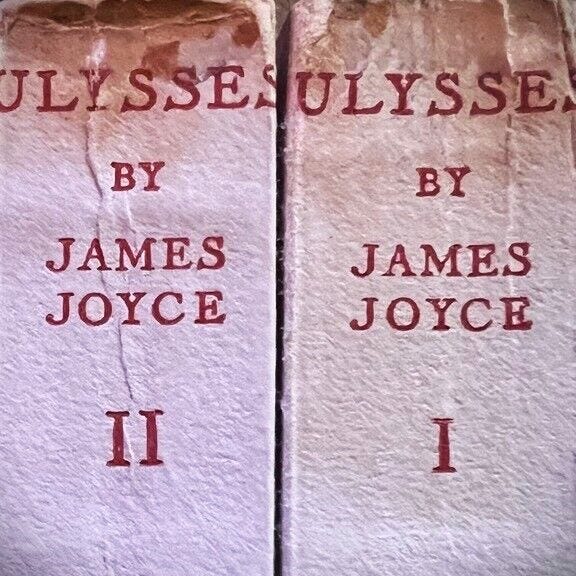

Ulysses on eBay

James Joyce, Ulysses (Hamburg: Odyssey Press, 1932), £TBC

This isn’t an association copy. But at the time of writing, there are three days left to bid for a copy of this two-volume paperback edition of Joyce’s novel. (“Very good . . . with a little general grubbiness” is how the copy is described on eBay; perhaps that’s not so bad as a description of the novel itself?) The highest bid, as I’m writing this, stands at £89, which sounds like a bargain. But presumably some people will be spending Christmas Day furiously driving up the price to something more like the going rate for such curious Joyceana.

It is always a treat to find little bits of ephemera tucked into old books...but I hate it when newspaper clippings are taped in. The acidic paper inevitably leaves a shadow.

I'm quite sure I've donated bits of ephemera to the cause, too - always grabbing whatever is nearby to use as a bookmark. I know that I returned a book to the library with a pretty rare 19th-century Chicago saloon card tucked into it once...

And Ulysses definitely has a little general grubbiness.