As every Janeite knows: the author of Pride and Prejudice was born on December 16, 1775; and so this year marks the 250th anniversary of her birth.

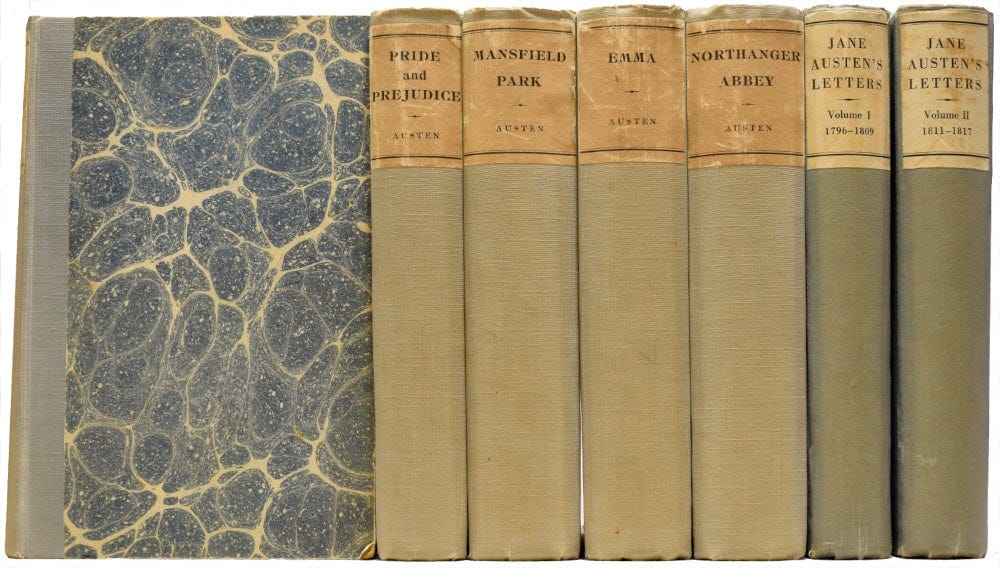

I’m taking that anniversary as an excuse to embark on an overdue re-reading of the novels, tackling them in leisurely fashion (or at least that’s the idea) over the course of the coming year. Six novels, published over a mere six years, from Sense and Sensibility in 1811 to the posthumous Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, which appeared together in 1817 . . . meanwhile, in contrast to Austen’s artistic ingenuity, glancing through my copy of Persuasion, I see that some of my teenage notes (“Objective correlative”, “time + past”) are going to prove galling entertainment in themselves.

Fame and acclaim were not always Austen’s lot. In contrast to the modern age of screen adaptations, tourist traps and tea towels, her books sold unevenly during her own lifetime. Pride and Prejudice was enough of a fashionable hit to require a new edition in its first year of publication (1813). By contrast, John Murray printed 2,000 copies of Emma in 1815 but had to remainder just over a quarter of them five years later. And although Emma was published in the US in 1816, and a few French translations appeared in Austen’s lifetime (starting with Raison et Sensibilité, 1815), serious international popularity would only come along much later.

This makes for an interesting publication history, to say the least – and I confess that the proverbial lottery win would probably send me off in pursuit of some of the more notable old editions of Austen’s works. (To read by the pool, of course.) There’s no shortage of decent options on the market at the moment – this “stunning box set” (£400), say, or this illustrated pocket edition of the 1900s (£1,250). Not forgetting the first edition of Sense and Sensibility in one volume (London: Richard Bentley, 1833; £3,500), the third overall; or the first edition of Pride and Prejudice in three volumes (London: T. Egerton, 1813; $175,000).

It seems that Austen prices haven’t exactly dropped in recent years. In December 2022, the BBC reported, five first editions of Austen’s novels sold at auction for just over £181,000; half of that total went on the copy of Pride and Prejudice, which sold for £92,000. (The least expensive, on this showing, was the combined first edition of Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, which sold for £6,400.) These copies’ previous owners had bought them for £5,000 or so, during the 1970s and 80s – ie, even adjusted for inflation, a fraction of the sum realized.

A year later, Austen’s own copy of Isaac D’Israeli’s Curiosities of Literature (1791) went under the hammer at Sotheby’s; signed by her on the title page, and sparsely underlined in pencil, it sold for $215,900. The estimate had been $100,000–150,000.

Maybe these are exceptional cases. But they are still a far cry from the situation in the 1930s, when Virginia Woolf bought the five volumes of Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso from Austen’s library for 15 shillings (c. £45 in today’s terms), as a Christmas gift for John Maynard Keynes. Woolf inscribed it for the recipient on the flyleaf (its previous owner’s name being inscribed on the facing page). Keynes eventually donated the book to King’s College, Cambridge (which has both a substantial Austen collection and a prior Austen family connection).

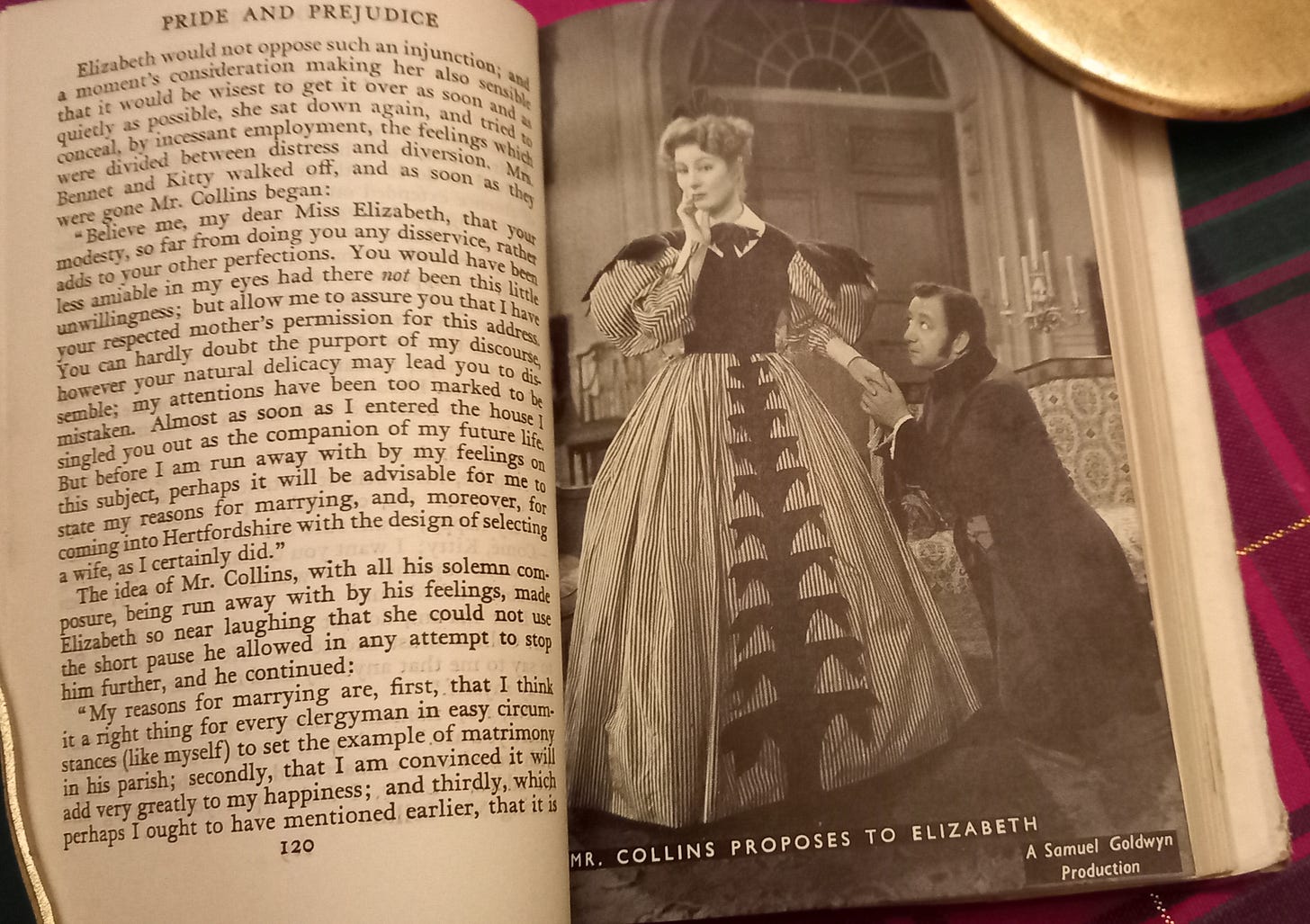

Building an Austen collection could be less challenging, however, than the headline-grabbing items of the past few years might suggest. For those who can afford it, there are nineteenth-century editions of the novels that sell for smaller sums (think three to five figures rather than six); and those of us who can’t might console themselves with related lines of pursuit, such as the tradition of Austen sequels and spin-offs that may be traced back to the continuations of her work by two of her nieces. (Only one was published: The Younger Sister by Catherine Hubback, 1850, based on The Watsons. The other was an earlier attempt to complete Sanditon, by Anna Austen Lefroy.) Or rather than shunning the egregious film tie-ins, how about chasing them up?

Another possibility: Valancourt Books has reissued the “horrid novels” celebrated in Northanger Abbey – The Castle of Wolfenbach by Eliza Parsons, The Midnight Bell by Francis Lathom etc – but it’d be interesting to fossick for their earlier incarnations. The first edition of one of these Gothic shockers, The Necromancer, sold at auction last year for £12,500.

Money – that all too Austenian subject – isn’t everything. A recent interview with a young collector of editions of Pride and Prejudice, Vera Jiā Xī Mancini, reveals a wholly different approach to building an Austen collection:

My most extensive collection consists of copies of Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen in various languages worldwide. However, I only collect copies from friends and family who bought the book while in the country whose language the book is in. I do not purchase copies online, as that defeats the purpose of the collection, which tells many stories of international travel and relationships.

This may be a collection that, as yet, only numbers thirteen books from twelve different countries, but isn’t there something admirable in its emphasis on sociability and forging connections across language barriers? One of those thirteen books is an Arabic edition from Cairo:

When I was fifteen, my father went to Cairo, Egypt, on a trip sponsored by the State Department with an NGO called Hands Across Egypt to give talks and educate people about working with differently-abled people. While there, he met with a young woman at a university who mentioned she was attending a book fair later that day. He told her about me and my growing love for literature, and she told him she shared my passion for Pride and Prejudice. She helped him get me a copy in Arabic from the local book fair. I love the artwork of this copy, with a hand-painted artistic style and the interpretation of Elizabeth Bennett as a woman with darker skin of Southwest Asian or North African descent with clothes resembling styles of the earlier half of the twentieth century. I feel connected with the young woman my father worked with, this depiction of Elizabeth Bennett, and this specific book in a unique way that I cannot fully articulate.

ICYMI: The sociologist Paul Gilroy has donated several hundred books to the radical bookseller Housmans near King’s Cross; the books go on sale on January 18 and “As with all our booksales we try to keep prices as low as possible with nothing over £5”. Elsewhere, Peter Harrington’s January sale is quite a sight. But it only lasts until January 13 . . .

Ditto!

Excellent stuff as always. And thanks for the Fine Books shoutout!