I can’t help it. There are still times when I try to introduce something like a sense of order to my bookshelves. Now the latest attempt has taken place, an impetuously undertaken chore among other chores; and in retrospect, I can see that it’s been yet another inglorious failure. Truly, the masterstroke of a simpleton.

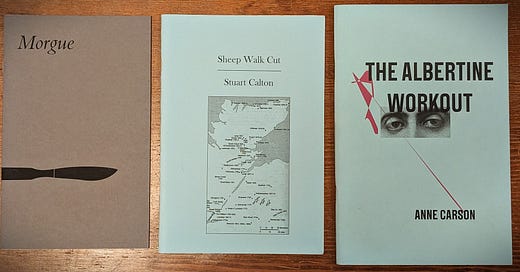

I’m talking here about poetry pamphlets. (Or chapbooks? Call them chapbooks, if you prefer. I like both.) See above. I’m talking about the bookseller Simon Beattie’s translation of Gottfried Benn (still available from Beattie’s website, I see), as well as Stuart Calton’s sequence of forty-five itching, glitching quatrains (London: Barque Press, 2004) and Anne Carson’s paragraphs inspired by Marcel Proust (New York: New Directions, 2014).

Like some but certainly not all readers, I have a weakness for slim volumes of verse, together with an even weaker weakness for even slimmer volumes of verse. A speciality of the smaller press, pamphlets tend to appear at poetry readings or book fairs rather than in the shops. (“Very few bookshops take poetry pamphlets, partly because, without a spine, they are not suited to being displayed on shelves.”)

I don’t possess anything like an exceptional collection of chapbooks. They’ve certainly accrued around me over the years, though, one way or another. Among the slim volumes on the shelf, they are the slimmer volumes that subvert the steady monotony of printed spines, stapled or stab-stitched, sometimes only a few pages long, sometimes making themselves known as nothing more than a colourful straight rule between their more ostentatious neighbours. But now I don’t know if this is the best arrangement or the way to guarantee losing track of the blighters completely.

Either way, all I meant to do was glance idly through one or two of them. But then I started taking the pamphlets off the shelves, just to confirm, more or less, what was there. But also: partly in the belief that they’d be better protected in a box or two of their own. A shoebox or two, maybe. At some point, this idea became more attractive than the prospect of filing them away again in their former locations.

Here are several of them, together with a few quotations and annotations, in the spirit of celebrating this small wonder of a format . . .

I try to bring people in from the sidelines.

I am at my best with underdogs and misfits.

My mother would say to me,

You and your lame ducks.

(Rachel Curzon, “Question”)

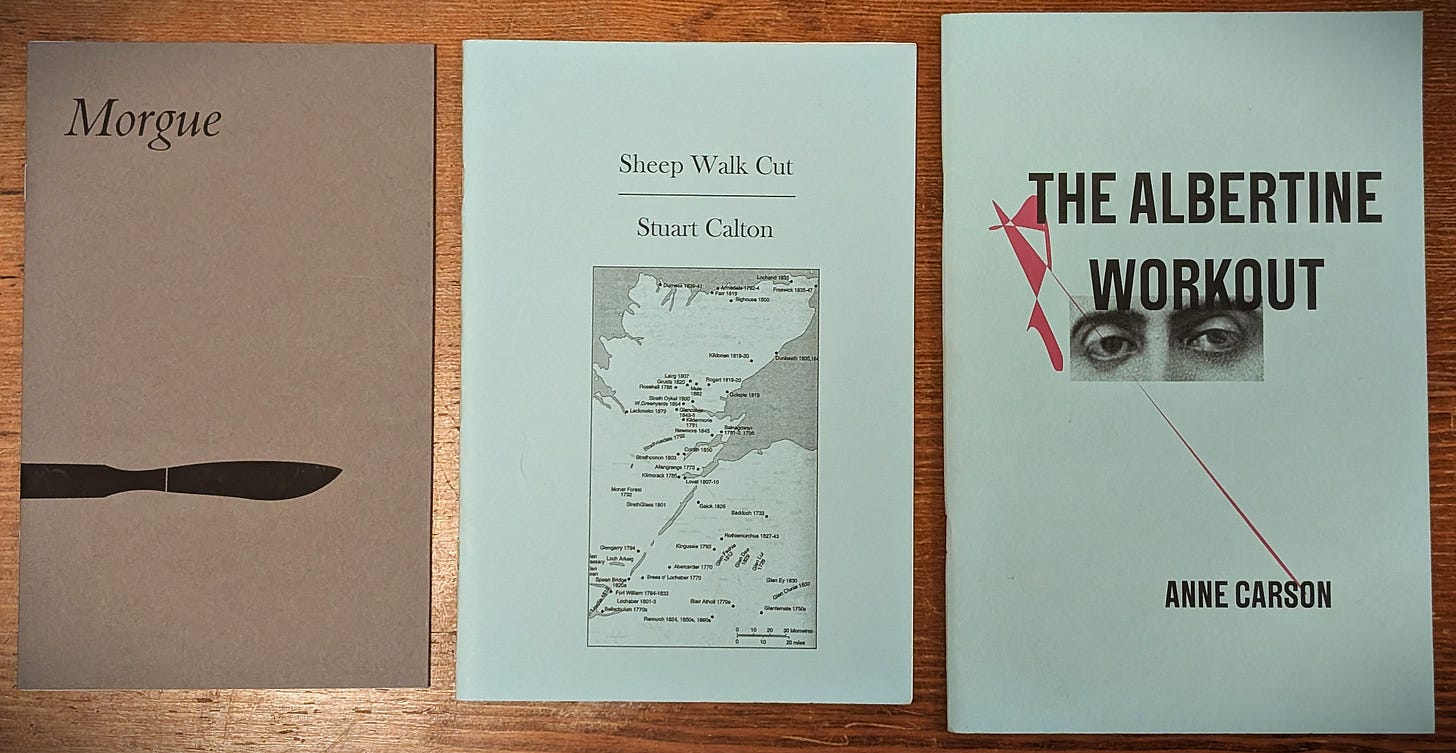

Rachel Curzon’s pamphlet in the Faber New Poets series (London: Faber, 2016); Will Eaves’s Small Hours (Brockwell Press, 2006); and T. S. Eliot’s Burnt Norton (London: Faber, 1941), a third impression, a present from an English teacher and therefore a reminder of dim, early efforts to follow the echoes inhabiting the garden, etc. If I understand the chronology, this first of Eliot’s Four Quartets had already appeared in print before the Second World War, in Eliot’s Collected Poems 1909–1935 (1936). But it was reissued separately, and both East Coker and The Dry Salvages were in print by the time this third impression of Burnt Norton was issued.

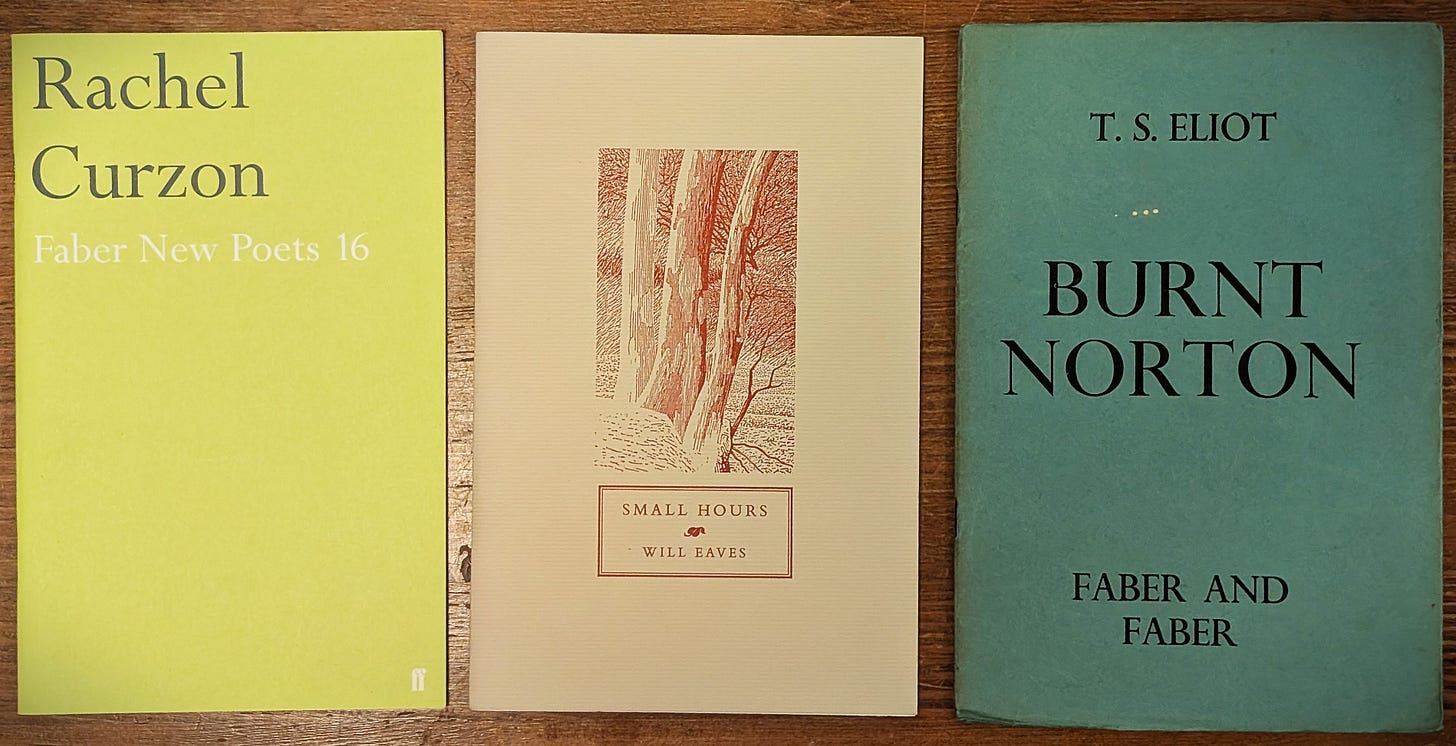

Festival Nights by Gavin Ewart (Leamington Spa: The Other Branch Readings, 1984), signed by the poet, characteristically rollicking stuff; The Angelsey Leg by Jo Field (Glenrothes: Happenstance, 2015), published to coincide with the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo (the limb in question being that of Henry William Paget, Earl of Uxbridge, who lost it while commanding the cavalry); and Ex Officio by Duncan Forbes (Hitchin: Cellar Press, 1973), an accomplished early poem by another former teacher.

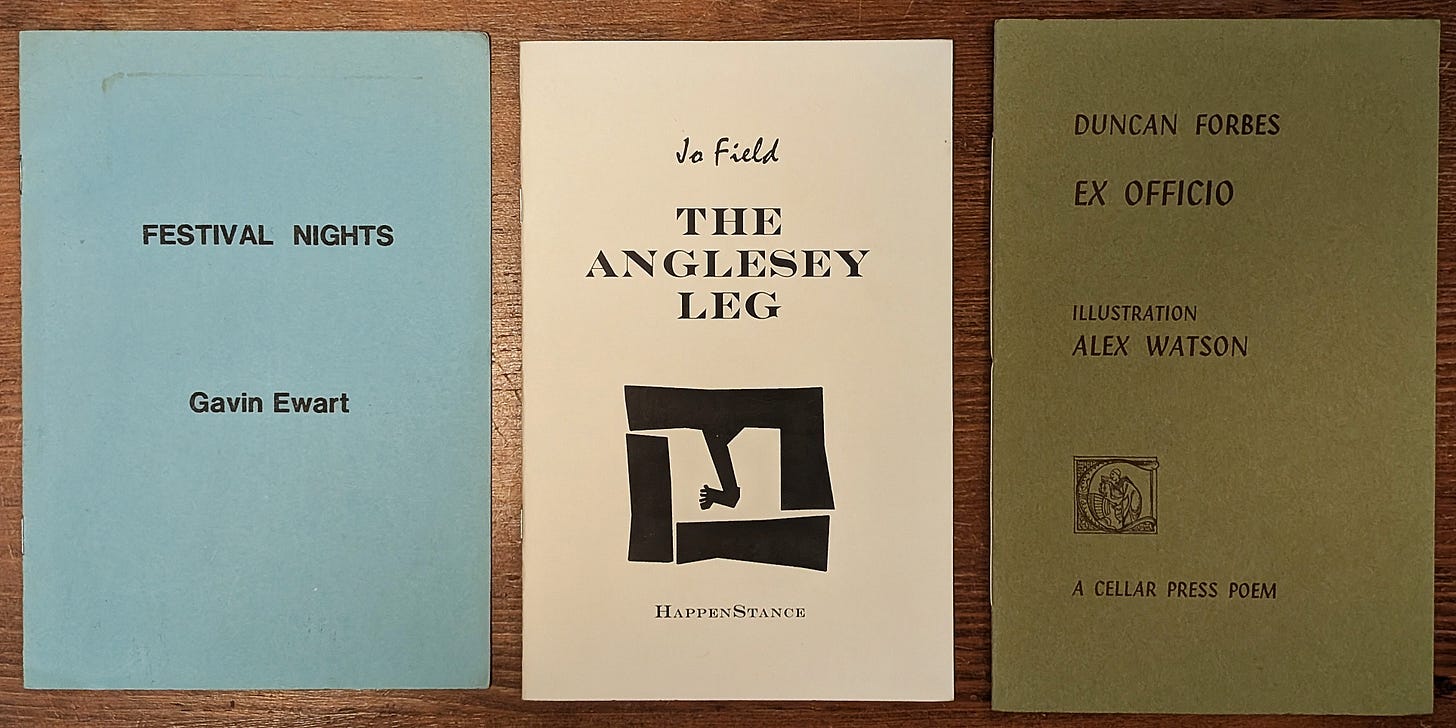

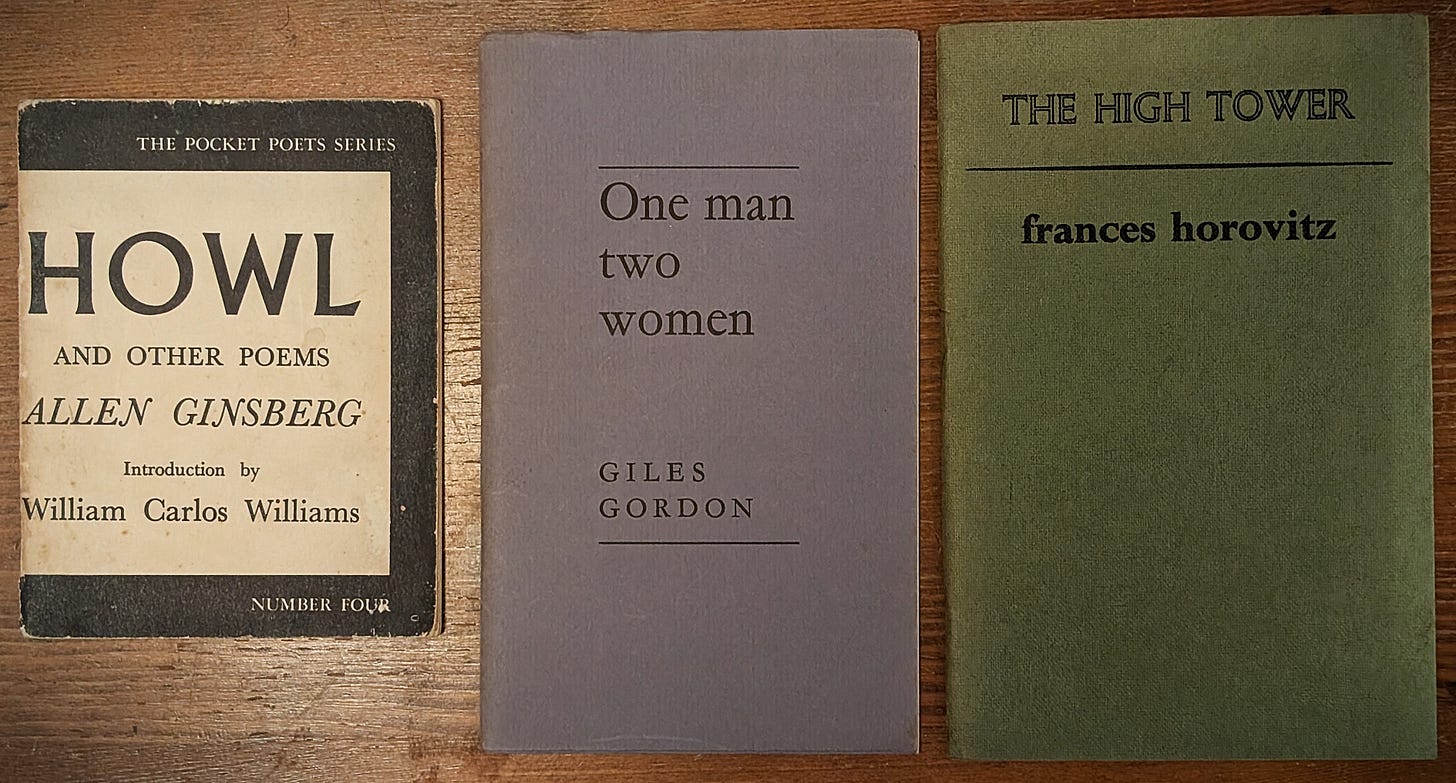

Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and other poems was first published in October 1956; I believe a signed first edition could set you back £12,500. I’d be surprised if my scuffed eighth printing (San Francisco: City Lights Books, September 1959) cost me more than a few quid. It’s been hanging around for a long time, to no great purpose. Also pictured: One man two women by Giles Gordon (London: Sheep Press, 1974), a sequence of thirteen poems that came with a short letter from Gordon to a friend (“Could you manage Wed, if you’d like to see A Finney in Sergeant Musgrave?”); and The High Tower by Frances Horovitz (London: New Departures, 1970), an elegant marred only by a fantastically clumsy ownership signature opposite the title page.

Late in a garden I turn each page.

The day’s evening waits in the wings

old words singing by heart almost

till I reach that roll-call in parenthesis:

(Enter . . . Cobweb, Moth, Mustard Seed).

(Angela Leighton, “Humming-Bird Hawk Moth”)

Here are three examples of pamphlets from presses doing interesting things, I reckon, in different ways: Sex 2 by Camille Kingué (If a Leaf Falls Press, 2024); Five Poems by Angela Leighton (Thame: Clutag Press, 2018); and Words and Music by Andrew McCulloch (London: Melos Press, 2023). Sam Riviere’s If a Leaf Falls emphasizes “appropriative and procedural writing processes”. Andrew McNeillie’s Clutag aspires to “high but not precious production values”, and celebrates its twenty-fifth anniversary this year. William Palmer’s Melos has published six McCulloch titles, of which this is the most recent.

A Cézanne Haibun by Maitreyabandhu (Sheffield: Smith Doorstop, 2019), to which I was led by the aforementioned author of Small Hours; The Column Inches by Tim Wells (London: Tangerine Press, 2014), consisting of three wry poems in commemoration of “Britain’s legendary sex goddess” Mary Millington; and At Raucous Purposeful by J. H. Prynne (Talgarreg: Broken Sleep Books, 2022). The most beautifully printed of this trio is the Wells, a classic Tangerine product. The other two are serviceable if not beautiful.

*

ICYMI: Any Amount of Books is looking for a deputy manager. Also a part-time bookseller. Further evidence of the long-standing British obsession with the Classics may be found here. A mere $3,500 would buy you the copy of Edith Wharton’s Artemis to Actaeon and other verse (New York: Scribner’s, 1909) that Wharton inscribed for Frances E. Thayer, the woman who “almost certainly” typed up the book for her.

As a publisher of poetry pamphlets I am glad to see them celebrated. One common misconception about the poetry pamphlet is that it is some sort of nursery slope or first attempt at publication. Although it often is this and Rack Press has “launched” a few careers, it is also a format favoured by well-established names. The message, however, has not got through to everyone. Trying to interest the Aldeburgh Festival some years ago in one of our pamphleteers they replied firmly: “We have a limited amount of space for poets at the pamphlet stage."

Sir, you are a gentleman.