I’d been warned. The pebble-dashed house down the street was said to contain a life’s acquisitions, heaped high; in fact, over time, sheer acquisitiveness had rendered many of the rooms inaccessible.

Now the old lady, the house’s single resident, had died. A mutual friend had asked me to take a quick look at the books, of which there would be many, probably worth nothing much, or nothing at all, but you know how heirs can be — it would be good to be sure — it shouldn’t take you more than half-an-hour or so.

I wasn’t sure if I could help very much. But I couldn’t help feeling nosy.

And the rumours about the place were true. Ivy gripped the garden. The hallway, when my friend let me into it, proved to be narrowed to half of its full width by a welcoming committee of heavy wooden furniture, ornaments, dolls and more ornaments. A wardrobe blocked in a bookcase, on which I could make out the colourful jackets of rows of hardbacks; next to them was a tower of unpromising paperbacks in grocery boxes.

The rest of the ground floor was taken up with: a large front room almost entirely taken up with mounds of clothes, as far as I could see; an equally large second room, relatively clear, but still loaded with clutter; a small bathroom in a state of disuse; a kitchen in which the owner had apparently spent most of her time, crouched by the heater; and, besides a grand staircase, a corridor designed to link one side of the house to the other, but absolutely impossible to traverse, being blocked at both ends by furniture. The interior of the house certainly didn’t smell awful, but there was plenty of grime and cobwebs hanging like curtain swags. Much of the clothing, I gathered, had been purchased in local charity shops, and brought back here to be arranged in neat but looming edifices on beds, chairs etc.

Upstairs there was more of the same.

And sure enough, this lonely house came with a library of sorts, divided between bookcases, boxes, odd shelves. I was left to sift through them — or rather, to sift through whatever I could actually reach.

Even if I was about to get it all wrong, I felt that I’d just let myself in for a taste of what many dealers in second-hand books must endure all the time. Fossicking amid the relics of someone’s long life as a hoarder, in what was once a family home, as carefully and quickly as I could, staying alert for interesting items, but without any great expectations of finding, say, a £56,000 Chinese Bible in the attic.

With the array of exquisitely creepy dolls in mind, however, I wasn’t surprised that I did find plenty of handbooks and histories on the subject. There were also children’s books of a certain vintage, assorted art histories, Miss Read in hardback, Hammond Innes in paperback. A legion of tatty Readers’ Union and Book Club Associates editions. A set of three stout volumes at the foot of the stairs: The Reader’s Digest Complete Library of the Garden. It had already been suggested that some of these volumes would end up being recycled if the charity shops wouldn’t take them.

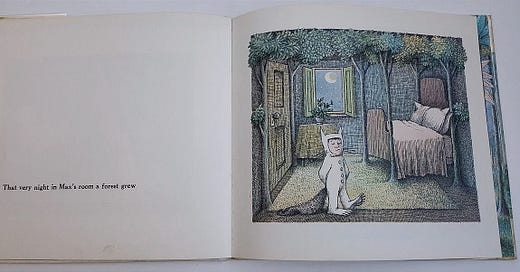

Having frowned unproductively at the various bookshelves beyond my reach, I reluctantly made my way back to the front door, where those grocery boxes of paperbacks were piled up. Still no Chinese Bible. But I did find a few exceptions to the general run of things: a few early Penguins; a couple of “rare” novels (that adjective must be the most abused word in book-dealing); a turn-of-the-century set of Bulwer-Lytton; a third impression of the UK edition of Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak. (A copy in a similar condition, with a slightly grotty dust jacket, is for sale at the moment for £100.) None of it in pristine condition, in keeping with the rest of the house. But maybe worth passing on to whoever’s inherited it all. Apart from the endless second-hand clothes, I reckon the books are probably the least valuable part of the house’s copious contents.

And I left having reminded myself that hoarding really is not the same thing as collecting. At least that’s the self-justifying observation to which I cling as I contemplate my own efforts to bring order to a few unruly shelves. (I’m not that bad — yet — am I . . . . ?)

*

ICYMI: The Edinburgh Book Fair is coming up. A new catalogue from Peter Harrington runs from Martin Luther and Boccaccio to Neuromancer and A Computer Glossary. “Soon, this solid citizen is tripping, catastrophically, on acid.”

Intrepid, Michael!