Hammamet, Tunisia, 1973:

I cannot really relax because there is the difficult problem of getting the books back to England . . . If the worst comes to the worst I will just have to leave my clothes behind and should be able to get the 55 volumes of Curtis’s Botanical Magazine into my suitcase.

Brussels, May 1987:

. . . after 25 years as a bookseller, now even with a certain International Standing, I still have no stock to speak of and a £10,000 overdraft at the bank. And I read recently that the average man has seven pairs of trousers. I have two.

Paris, 29 June 1990:

I’ve decided to make a short week-end trip to Paris [to] look at the fleamarkets and the Sunday bookfair. Rather absurd. . . . This journey has taken 14 [hours], plus nearly an hour to find somewhere to park my car.

Istanbul, May 2002:

I have been to a few bookshops. Only two detained me for more than a moment. One was the English Bookshop in a basement along the street from our hotel. Very bare and tidy, looking as much like a video shop as the owner could manage. . . . my other shop . . . was in the book section of the Grand Bazaar. A tiny cupboard-like place, very neat. A quick glance showed me it was as dud as all the others, but then I spotted a copy of Séguy’s Papillons, one of the rarest and best pochoir portfolios, leaning against the back wall. This was “Ming Vase in an Oxfam shop” stuff. I took it down expecting the man to say $2000 or $10,000. The price was $200.

It was the painter Howard Hodgkin who first read these words, in the letters his friend David Batterham sent him during book-buying expeditions. No reply was expected or required; writing these letters to Hodgkin was simply a way of beguiling the lonely hours in cafes or hotels.

Batterham’s fellow book dealer George Ramsden later published these letters as Among Booksellers (York: Stone Trough Books, 2011), with a foreword by Hodgkin. They testify to the idiosyncratic nature of a job that requires idiosyncratic people to do it. “Booksellers are often rather odd”, Batterham admits in his introduction. “This is not surprising since we have all managed to escape or avoid more regular forms of work.”

Among Booksellers came to mind as I was reading the spring issue of the Book Collector, which has just been published. Among other items here is the latest instalment in Sheila Markham’s long-running series of interviews with members of the book trade. The interviewee: Peter Kraus, the nephew of the eminent Hans Peter Kraus and owner of Ursus Books in New York.

Kraus has been in the rare books business for decades, having been all but born to it. When he was twelve, his uncle put him on his mailing list for catalogues; he also took him to his first sale at Sotheby’s. “I sat beside him, petrified of making a movement that might be mistaken for a bid.” From these beginnings, Kraus ended up working for “HPK”, then setting up on his own in 1972, and that business is still around today.

It’s a good story, involving cameos by folks such as the artist Leonard Baskin and Jay Last (“a founding father of Silicon Valley” who also happened to be a “passionate collector of lithography”) — I don’t mind a spot of name-dropping in these tales of book-dealing lives. Much of it sounds like great fun. Kraus ends the interview on a cautionary note, though, that speaks to modern times rather than the past:

The internet is catastrophic for my business and, I believe, for the rare book trade in general. It wiped out book shops and the opportunity for young people to learn the business in the best environment. Gone are the days when Warren Howell educated an entire generation of booksellers in his shop in San Francisco. The internet also enabled ignorant people to sell books. I’m not sure how many of them know how to collate a book — not many, given the number I order online and then have to return because they’re not complete.

Would other dealers in rare books agree with this assessment? It certainly echoes the expressions of scepticism or reluctance to move with the times — that most disturbing of notions — that pop up here and there in the Markham interviews. In his interview, for instance, George Ramsden sighs:

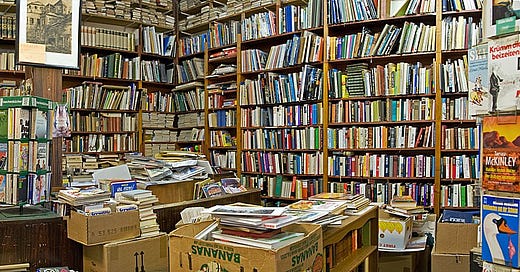

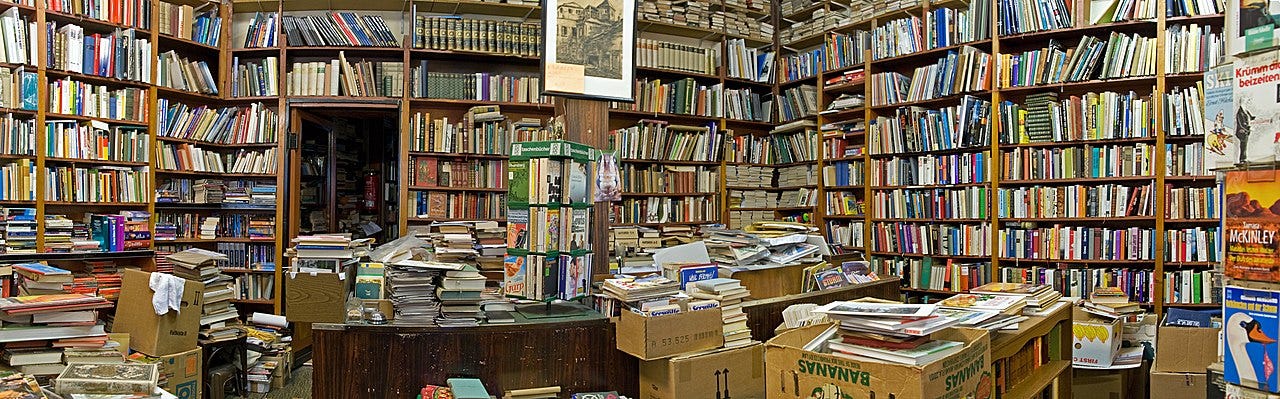

At some stage I will probably have to learn about the Internet. Although I find it good for reference, I much prefer to look for books in a bookshop. Almost anybody’s stock is an education. It amazes me how people come into a shop, hardly stop, and walk out again – even people in the trade. If a stock is any good at all, it’s worth investigating, slowly.

It’s still possible, Kraus concedes, to approach rare book-selling “with passion, curiosity and the humility to recognise that you will never know it all”, and find that there are “still tremendous possibilities out there”. The name-dropping isn’t just that, it turns out: grasping those possibilities takes good teaching, inspiring friends and so on. And it seems that it does require a certain kind of person to undertake a Batterham-esque expedition to Hammamet, Paris or Istanbul, in search of the bibliographically tremendous; and then to work out what to do with your treasures, should you find any. Is that a different personality type from the bookseller who hasn’t had the educational advantages to which Kraus here alludes?

There can be a wistful element to reminiscences about the book trade that some will find exasperatingly rose-tinted. Warren Howell, for one, doesn’t sound so great when you picture this “massive hulk of a man” yelling at a timid young clerk, in his first year on the job, “Well, if it isn’t my friend, the world’s greatest bookseller!” (See Jeremy Norman’s short memoir of his former boss, linked above.) There were always the bargains in the Grand Bazaar or a humbler counterpart. There were almost always names to drop, cantankerous customers, memorable fellow eccentrics behind the counter. (And there were barely any women involved because, you know, only pipe-smoking chaps permitted, eh what?)

“Booksellers are often rather odd . . .” I’m hoping that this is still the case. That the characterful oddities and handed-down expertise haven’t been eroded along with the old ways of doing things, for good or ill, and that book-dealing still represents, for anyone who goes into it, a great escape from work in its all too regular forms.

*

Also in the spring issue of the Book Collector: parodies of modernist poetry; some forgotten film books; Alice in Wonderland transferred to Naval Intelligence; and more.

Please share Bibliomania if you’ve enjoyed it!

What a delightful read. I have a dream of opening up a little bookshop in Italy. I hope I’m odd enough to join the ranks of booksellers.