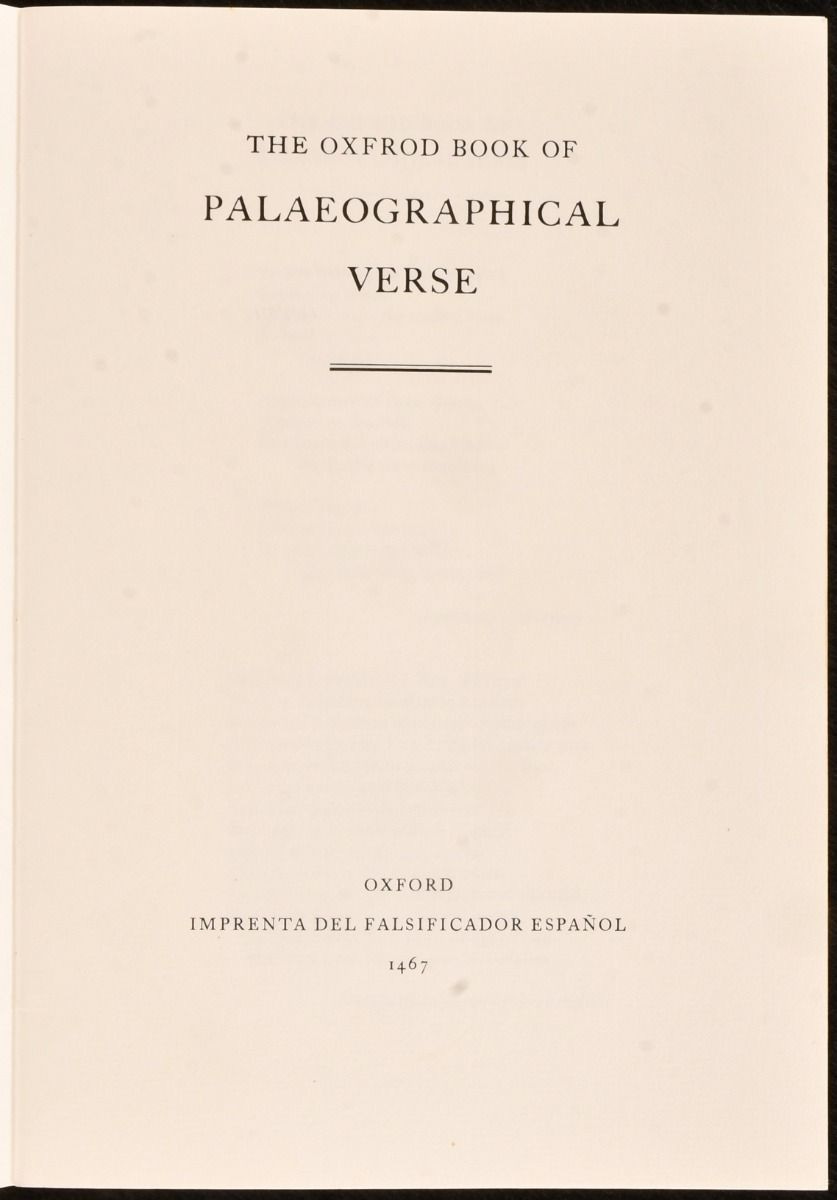

Copies are scarce, or are claimed to be: “Limited to fifty-six copies”, the colophon states, “of which forty-eight are for sale”.

The publisher?

Imprenta del Falsificador Español (ie, the “Spanish forger”).

The year of publication?

1467 (though sightings appear to date back only as far as c.1985).

The title? The Oxfrod [sic] Book of Palaeographical Verse . . .

The editor? Well, that would be telling. In case minor matters such as editorship (or even authorship) matter to you, it may be worth mentioning that this short book has occasionally been linked with the name of that bookman par excellence Christopher de Hamel (formerly of Sotheby’s, member of the Roxburghe Club, author of Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts etc).

More important by far is that it is only by means of this notable anthology that delights such as this otherwise unknown sonnet by Shakespeare have been preserved for posterity:

Shall I compare thee to a Book of Hours?

Thou art more lovely and more intricate;

Rough hands do shake the ancient vellum quires

And someone’s crease hath dull’d the pristine state.

Sometime too hard have people read the lines,

And often are the gold initials dimm’d,

And ev’ry miniature sometime declines,

And edge, by binder’s knife, is trimmed.

Thy office of the virgin goes unsaid,

Thy calendar unsoil’d by greasy palms,

Nor shall thou mingle with the office of the dead,

Nor follow litany and penitential psalms.

So long as men can breathe, no eye can see

How long lives this: it’s gone to Tennesee [sic].

Who knew that there was already a trade in medieval manuscripts between Europe and the Americas in the 1590s? Or that a poet in London might already know by then of an American state called “Tennesee”, derived from the Cherokee?

Admittedly, it does seem strange that an “Oxfrod” (Oxfraud?) anthology published in the fifteenth century should include equally distinguished examples of palaeographical verse from later centuries, by poets from Milton (“What though the field be glossed / All is not glossed”) and Wordsworth (“I wander’d lonely through the stacks”) to Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Tennyson, Kipling and Chesterton.

There is even room here for the odd nursery rhyme:

Cook-a-doodle-doo,

My books are overdue,

The Keeper’s lost his walking-stick

And doesn’t know what to do.

But what to do in the face of treasures such as the sonnet (another one, damn it all) by which Shelley is here represented?

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said that many ancient monkish tomes

Were housed in Cambridge . . .

And on a pedestal these words appear:

“My name is Monty James, Provost of Kings,

Look at my works, ye rivals, and despair.”

As a caveat, I’ll merely note that when The Oxfrod Book of Palaeographical Verse was belatedly subjected to a review, by Neal Street in the Book Collector (Winter 1991, pp. 583–8), the glaring omission of the “well-known” “Hymnal of St Richard Heber” was noted. (Heber: “Wholly, wholly, wholly undeciphered cursive” and so forth.)

Is there any more palaeographical verse out there? What a great Christmas gift to the world a further discovery (or two) would be . . .