(That’s a terrible title. Why “Touch and Go”? I have no idea. It’s late. I’m running late. Maybe that’s all there is to it . . .)

Anyway:

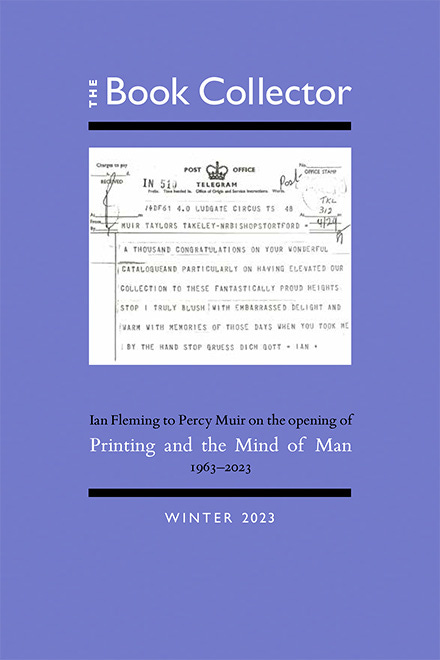

Just in time for this, the third instalment of Bibliomania, the new issue of the Book Collector has arrived. Praise be.

It includes the journal’s regular features – book news, an auction report, an interview by Sheila Markham, this time with Simon Lawrence about his life’s work, the Fleece Press – as well as my grimacing review of a book called The Gutenberg Parenthesis by Jeff Jarvis. For the most part, though, as the cover makes obvious, this issue is given over to celebrating a certain biblio-anniversary.

(Full disclosure: as well as writing for the Book Collector occasionally, I’m on its editorial board. I’ve had no involvement with the production of this new issue, though. I’m just cheering from the side-lines.)

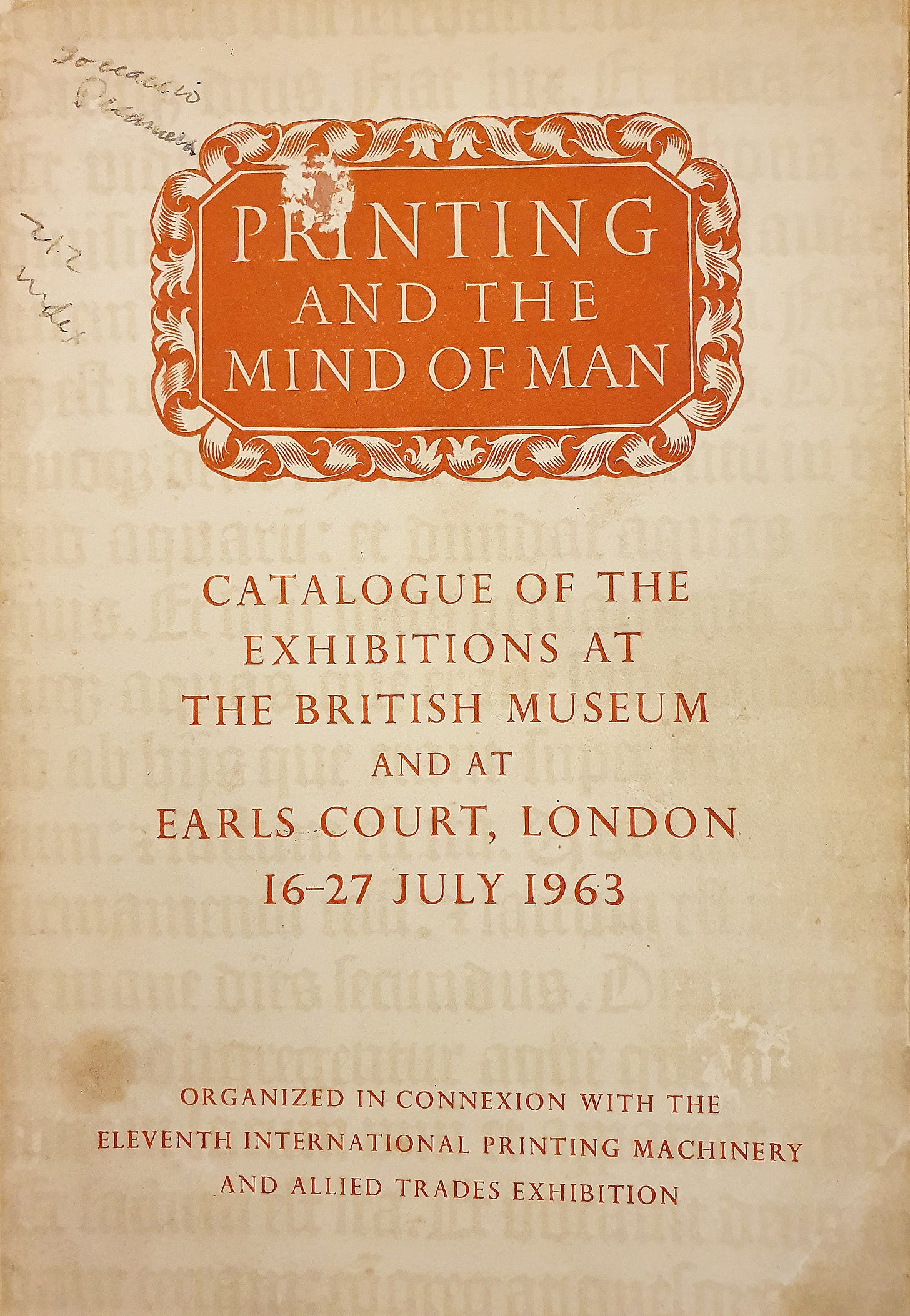

The exhibition Printing and the Mind of Man was held in July 1963, in three parts (one at the British Museum, the other two at Earls Court). An offshoot of a trade fair with a much more unwieldy name – the Eleventh International Printing Machinery and Allied Trades Exhibition – it aimed to show how printing in the West had developed over the past 500 years, but also to demonstrate its intellectual impact.

Exhibits ranged from the Bible printed by Johann Gutenberg et al in Mainz in the fifteen century to the Penguin edition of Shakespeare’s Sonnets of 1949 (and beyond, right up to 1962). Science, philosophy, politics, history were well represented by copies of hundreds of seminal publications: Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (Nuremberg: Johannes Petreius, 1543); Locke’s Essay concerning Humane Understanding (London, 1690); Kant’s Kritik der reinen Vernunft (Riga, 1781); Marx’s Kapital (Hamburg, 1867); and so on. Fiction and poetry were not so readily admitted, although the impact of, say, Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life among the Lowly by Harriet Beecher Stowe (Boston and Cleveland, 1852) could hardly be ignored.

In other words, PMM was an exhibition about books that advanced knowledge rather than books to be treasured for their authorial associations, fine bindings, scarcity value etc. A catalogue appeared that same year (see below for my slightly tatty copy), forming the basis of a book published four years later.

The problems with the whole project are easily spotted with hindsight – true to that stolid emphasis on the Mind of Man, for example, the exhibition featured a paltry number of books by women – but it was undoubtedly influential. For one thing, it clearly inspired some collectors, boosting the demand (and the prices) for various books. And I can recommend the catalogue if only as a substantial (if necessarily partial) bibliography of intellectual history.

This issue of the Book Collector tells the story in full: how it was hatched over lunch; the PMM personnel (including John Carter, Stanley Morison, Percy Muir, Nicolas Barker and Beatrice Warde, among others); what they rejected (an early book about the game of bridge, Marie Stopes’s Married Love et al); the logistics of “borrowing” some of the world’s most valuable books for ten days; the memorandum from the communist Allen Hutt putting them right about Marx.

A “PMM parlour game”, meanwhile, covers the missed opportunities. “Printing and the Child’s Mind” was just one subject that the selection committee “almost totally neglected”. Another omission – Kafka – gets an exhibition to himself next year at the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

The Book Collector dates back to the 1950s. Established in 2020, Inscription is, by comparison, a new kid on the block, and a truly welcome one.

Edited by Gill Partington, Simon Morris and Adam Smyth, it concentrates

not just on the meanings and uses of the codex book, but also the nature of writing surfaces, and the processes of mark-making in the widest possible sense: from hand-press printing to vapour trails in the sky; from engraved stones to digital text.

Each issue boasts its own artist-, poet- and writer-in-residence, and is published in a limited edition of 500 immaculately produced copies, LP-sized and accompanied by an actual vinyl LP and other paraphernalia. All four issues published so far have also been themed, beginning with “Beginnings” before moving on to “Holes”, “Folds” and, now, “Touch”.

That theme happily leads the reader down various different paths (garden paths? flight paths?). “Noli me tangere?” asks a poem by Vona Groarke. “Too late for that . . .” Matthew Shaw writes about the handling of books in institutional special collections, an act that is perhaps developing fresh significance in a time when “the primary interaction with pre-nineteenth century books” for many students and researchers is via the digitized facsimiles offered by commercial firms (“including the aptly titled Alphabet (Google’s parent company)” as well as projects funded by “government (particularly European) research council and philanthropic funds”. Taylor Hare and John Gulledge trace the ways in which blind readers of the nineteenth century bore the marks of the reading process on their skin; their essay opens with the testimony of Helen Keller, in 1909, who said that

“years ago, when I had a copy of Milton in Roman type”, and the act of touching the book’s grooves and contours had caused her finger to bleed: “a streak of blood followed my finger over the rough type, marking my path through Paradise”.

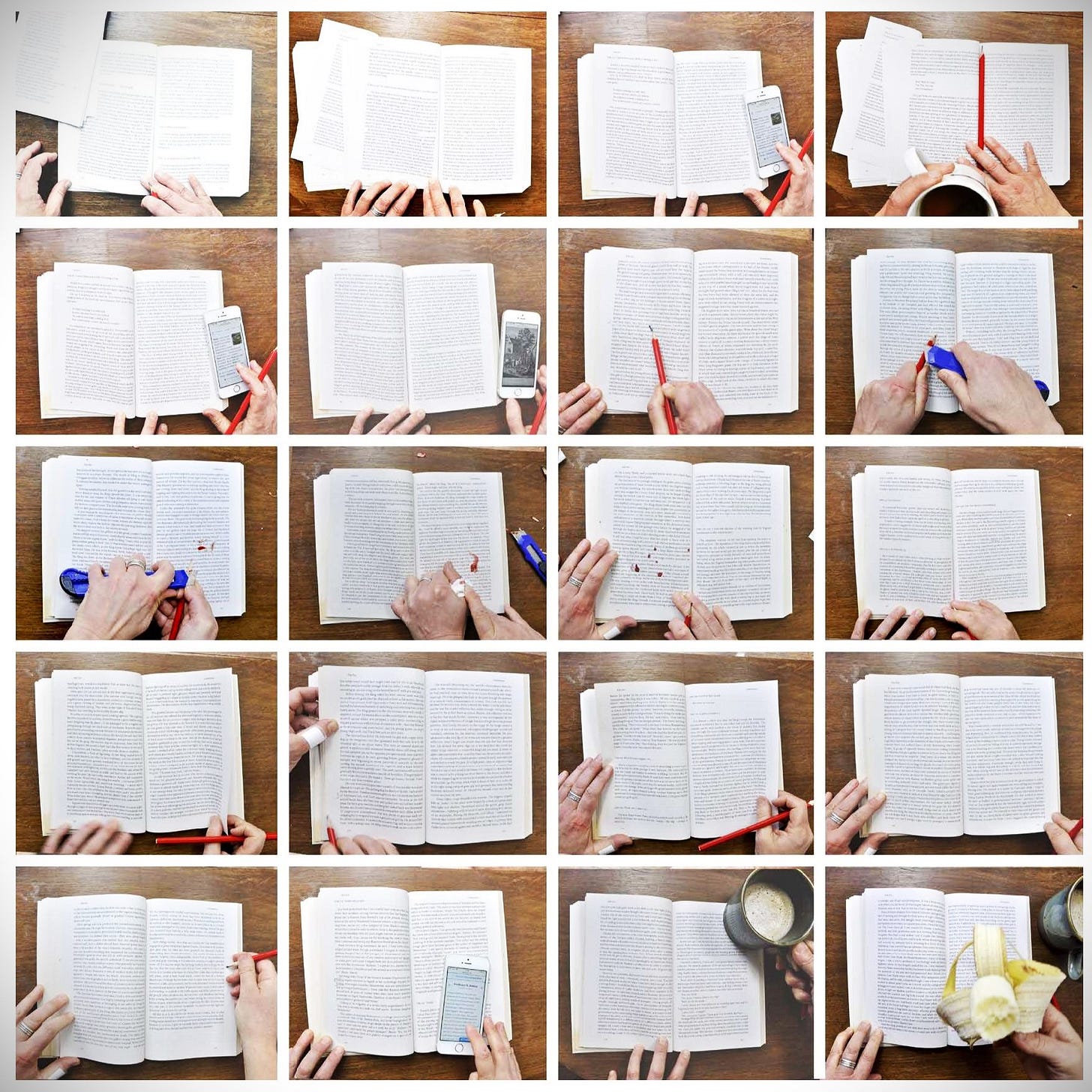

See below, by contrast, for images from Gill Partington’s Reading/Handling/Editing: Pale Fire (2021), setting the Nabokov’s Charles Kinbote and his “erudite if prolix digressions” against the distractions of a “ham-fisted and oddly literal” reader, “attention flitting between snacks, SMS conversations and the novel itself”. Here “mise-en-page gives way to mess on the page”.

You can read Inscription online, which is useful but less fun, I think, than the haptic experience it offers in its physical guise.