Last October, an auction of books took place at Sotheby’s in New York. Various rare book dealers and private collectors attended in person, bid online and by telephone; over two sessions and 327 lots, they spent about $3.7 million between them. What was all the fuss about?

I’ll come back to that. But for now, the short answer is:

Aldus Manutius.

Or, to use a typeface that originated with the press he founded:

Aldus Manutius.

To many in his lifetime, to be sure, “Aldus Manutius Romanus” – a public figure, internationally renowned. He was born around 1450, merely as Aldo Manuzio, to an affluent family in a town called Bassiano, about 46 miles south of Rome. The acquisition of a deep humanist education, in keeping with the most advanced ideas of the time, led Aldus to make the acquaintance of Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, which led him to become the tutor to that philosopher-prince’s nephews in the town of Carpi in Modena, which led to them lending support to his scheme for a printing press . . . which led him establishing one, in the early 1490s, in the Most Serene Republic of Venice.

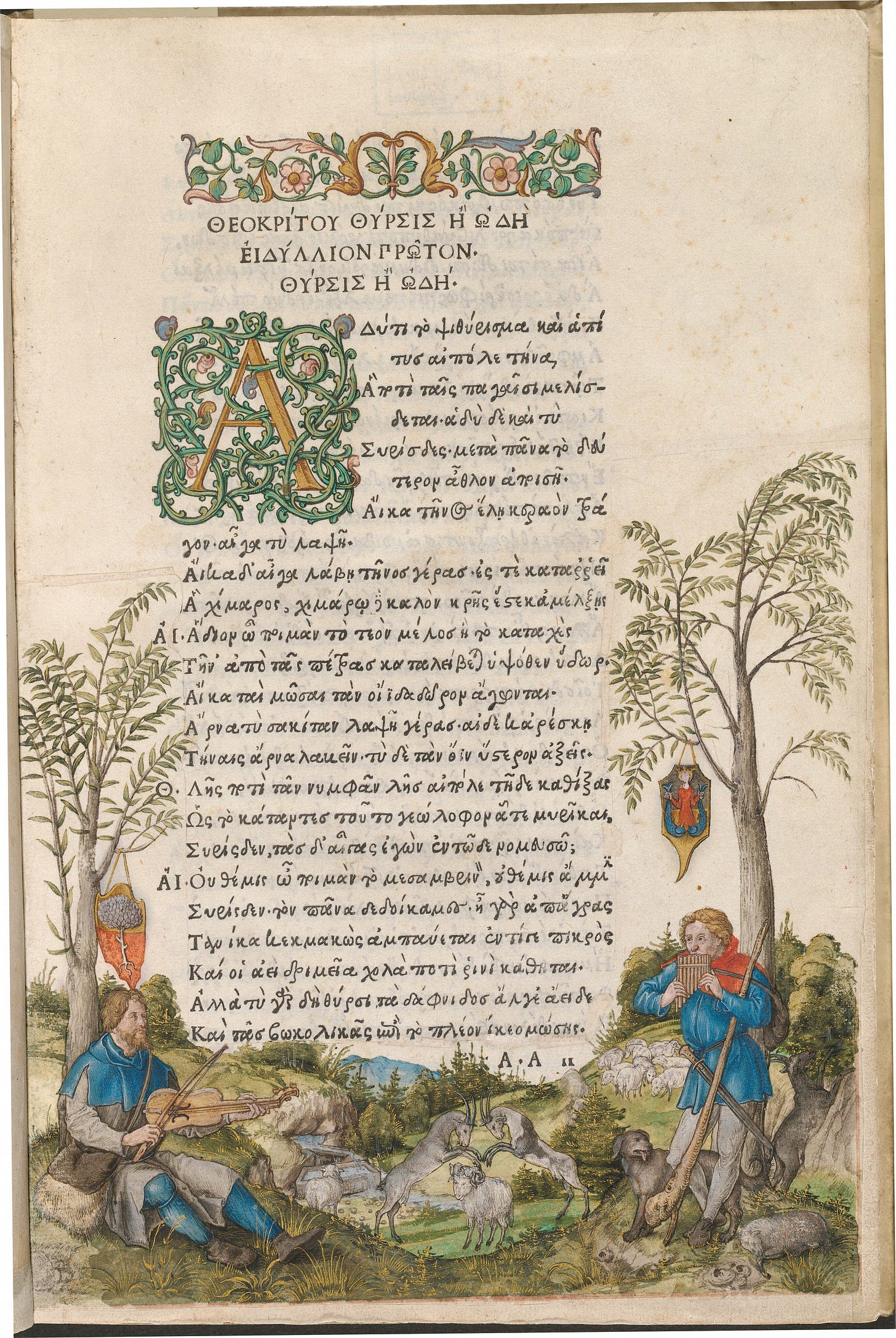

It was there, in Venice, that Aldus set up shop and made his name with a series of publications that promulgated an ambitious, humanist programme of literature, and came to constitute a seminal achievement in the history of the printed book. Aldus published the first printed edition – the editio princeps – of many works that had previously only existed in manuscript. To Erasmus, he was the “Prince of Printers”.

The seminal achievement is twofold at the least. On the one hand, there are the technical advances that took place under Aldus’s watch. His books feature the first italic type as well as a much-refined roman one. Beginning with the works of Virgil in 1501, meanwhile, he started producing libelli portatiles, portable books that would fit in the hand. These are often hailed as the ancestors of the modern paperback.

Perhaps in a world of pocket-friendly paperbacks this doesn’t sound all that astounding a transformation. But as Oren Margolis explains in Aldus Manutius: The invention of the publisher, it denoted a novel sense of why a reader might pick up a printed book. For one thing, “reading for leisure” was an activity that was being consciously cultivated here. Heavy folio volumes were for the study, the library, the church. Margolis quotes Machiavelli’s description of what it meant to be able to take literature out into the world:

Leaving the woods, I go out to a spring, and from there to my aviary. I have a book under my cloak, either Dante or Petrarch, or one of the minor poets, such as Tibullus, Ovid, and the like: I read of their amorous passions and of their loves, recall my own, and take a little pleasure in this thought. Then I shift myself down the road to the inn . . .

That was in 1513, by which time others were learning to copy Aldus’s approach – a sure sign of his success. Besides those rivals who published under their own names, such as Filippo Giunta in Florence and the peripatetic Gershom Soncino, there were also piracies, such as those made in Lyon that Aldus condemned, in 1503, for the “Frenchiness” of their typography.

This imitability leads to a second crucial point about Aldus’s achievement. His most significant predecessors had come to print with movable type from a background in craftmanship – Johannes Gutenberg the goldsmith, for example, or Nicholas Jenson the metalworker. Aldus did not himself cut those pioneering italic or roman types: they were the work of Francesco Griffo, his punchcutter, who fell out with him and went to work with Soncino. Aldus was, instead, a scholar with aspirations to grasp the potential of the printing press for spreading knowledge. Hence Margolis’s punning subtitle, The invention of the publisher, inviting the reader to weigh the technical advances of the Aldine Press against the ideal vision of the publisher as the visionary overseeing that press’s work.

Hence also the works that Aldus chose to publish, most of them featuring his celebrated emblem of a dolphin wrapping itself around an anchor – 134 editions in a period of about twenty years, sixty-eight of them in Latin, fifty-eight in Greek and eight in Italian – although the focus in this new study narrows to consider just a few of them. With good reason. Margolis’s book is, as I read it, an exercise in intellectual archaeology. He seems less interested in how Aldine books were printed than in what was printed and, above all, why. I don’t mean he’s not interested in the technicalities or the contents at all – just that excavating their meaning for Aldus and his contemporaries appears to be his priority here. The recovery of an idea. Rather than a meditation on, say, the deployment of the semi-colon in Pietro Bembo’s De Aetna (1495/6).

Framed by an introduction and an epilogue, the four long chapters of this book trace Aldus’s progress through the influence of those Carpi connections on his work; the significance for his oeuvre of “the most celebrated and strangest book of the Italian Renaissance”, the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (1499), reckoned to be the work of Fra Francesco Colonna; what it means that the italic type saw its first appearance in his edition of the Epistole of St Catherine of Siena (1500); and the later evolution of his “project of self-invention”, by which he came to publish Erasmus, as well as those handily portable books. This is only to pick out the course Margolis charts in the barest fashion, though – each chapter explores its subject with painstaking nuance.

Self-invention, for example, appears to have necessitated writing prefaces hailing the civilizing benefits of putting ancient Greek literature into print, as well as emphasizing the “athletic heroism of the enterprise”. (The “intellectual machismo” to which the whole humanist project was prone was not, however, always mirthless: Aldus joked about being so impressively busy in his Venetian shop that “there is scarcely even time to blow my nose”.) A “tension between accessibility and exclusivity”, meanwhile, entailed printing “large print runs” of those libelli portatiles (“another 3,000 or more for Catullus”) while also striving to maintain “a reputation for excellence, rarity and quality”. If there is a tendency to the grandiose in Aldine rhetoric, Margolis is not taken in by it. “Aldus is building a library which has no walls save those of the world itself”, Erasmus writes the expanded edition of his Adagia (1508). “Reading this”, Margolis remarks, “one would struggle to believe that the everyday material reality of the dolphin and anchor was surely to swing outside a Venetian printing shop like a pub sign.”

There are some overstuffed sentences here, and a prose style that occasionally exhibits amusingly belle-lettrist proclivities. Margolis will mention, say, satire and tragedy as two genres that Aldus, in 1500, “had not yet published, but would soon”, but not bother with the specifics. Skipping the mere bibliographical details is also to omit a warning, in David McKitterick’s words, that those legendary editiones principes “were themselves sometimes based on poorly chosen late manuscripts”, and suffered from misprints and rushed proofreading.1

But this wariness about Aldus’s work is not entirely lacking, and there are also numerous fine insights here into the world as Aldus conceived it, together with a pervasive sensitivity to print culture in this particular time and place. It is also good to see that Reaktion has done Aldus proud, with some mostly well-reproduced illustrations, such as two portraits, on facing pages, of sixteenth-century gentlefolk brandishing their Petrarchini – possibly Aldine and certainly portable copies of Petrarch’s “fragments”.

Margolis ends with an assessment of Aldus’s legacy and the critical period immediately after his death in 1515. (The family continued the business until 1597.) This means that the wider story of his books, as they were collected even during his lifetime, is largely absent here. But then that’s a story that isn’t quite finished.

In the twentieth century, for example, a former investment banker called T. Kimball Brooker found himself collecting books published during the sixteenth century; he ended up with an “extraordinary library of more than 1,300 sixteenth-century French and Italian books in their original bindings”. It is this remarkable collection that Sotheby’s is selling (in a process that, begun last October, is set to continue into 2025). Brooker’s collection includes around 1,000 editions from the Aldine Press.

Brooker could perhaps claim some kinship with one of the earliest and best-known of Renaissance collectors, Jean Grolier (c. 1489–1565), who also felt a particular passion for these publications. Grolier acquired more than 200 Aldine titles, and had them sumptuously and distinctively bound. Even without such treatment, however, these remained highly desirable artefacts. A sale catalogue published in The Hague in 1720 was the first to give Aldine titles their own section, a clear mark of illustriousness; just over a century later, at a major auction in London, “Even the common books were said to have been sold at two or three times the estimates”.2 Some of Brooker’s books didn’t sell in New York. But I guess those rare book dealers who successfully bid for others may already be preparing to entice in those lucky souls who can afford to indulge a serious passion for Aldinity.

David McKitterick, The Invention of Rare Books: Private interest and public memory, 1600–1840 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 34–5.

Morning Chronicle, July 10, 1828. Quoted in McKitterick, 275.