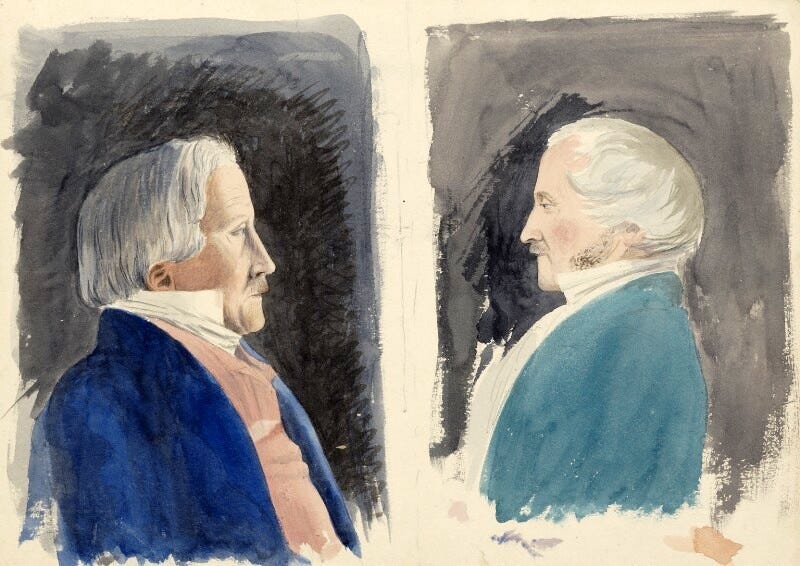

Around 1930 the young A. N. L. Munby (who was to become one of the world’s outstanding bookmen) met Sir Thomas Phillipps (who had been one of world’s most infamous bibliomaniacs).

Not that Munby and Phillipps met in person: the latter, born in 1792, had died in 1872. Much more appropriately, the two men met through Phillipps’s library. It was a fateful encounter.

Munby and his father were staying at Cheltenham when they made the acquaintance of a “handsome old gentleman” called Thomas Fitzroy Fenwick. This was Sir Thomas Phillipps’s grandson. Munby senior, a scientist and architect, visited Fenwick at his home, Thirlestaine House, and returned enthusing about its “vast library infested by some of the most interesting dry-rot he had ever seen”. Munby junior, as a budding book-collector, was allowed to visit in turn. He didn’t see the library itself; instead, his host had some choice items brought to the drawing room:

He rang the bell and the butler carried in two trays laden with manuscripts, which he placed before us. “The ninth-century Bede, sir,” he said, handing a book to Mr. Fenwick, who explained to me about its script and decoration. In the course of an hour I handled a score of manuscripts from the ninth to the sixteenth century, many of them of the highest quality . . . I left in a kind of trance, bemused by the splendour of it all. So this, I thought, is what book-collecting is really like.1

Or rather, as Munby would later establish, it’s what book-collecting is really like if you’re filthy rich, foul-tempered and incapable of focusing on anything else. And Phillipps hadn’t just owned a score of manuscripts; he’d accumulated possibly 60,000 of them “and nearly as many printed books”. It was “more than double the size”, the librarian Henry Bradshaw noted in 1869, “of the whole of our Cambridge University and College collections of MSS put together”.

A collector from his youth, he had been let loose on the world with a fortune of at least £6,000 per year, derived from his Mancunian father’s calico-printing business. Over five decades, he proceeded to buy an average of “about twenty manuscripts and twenty printed books each week”. The aim, although the ODNB takes this to be a joke, was simple. “I am buying Printed Books”, Phillipps told Robert Curzon, “because I wish to have one copy of every Book in the World!!!!!”

Luckily for him, Phillipps had come into his inheritance at just the right moment to take advantage of the vast dispersal of books and manuscripts that took place in the wake of the French Revolution (but after the price-inflating boom of the early 1800s). He spent extravagantly, forcing him to borrow, and acquired an international reputation for his activities. He wasn’t alone in suffering from a mania for the acquisition and preservation of old books and vellum manuscripts (far from it). To many, there was an “aura of romance” about such materials, with their origins in barbarous days of yore. Dubbing himself a “Vello-maniac”, Phillipps seized on all the manuscripts he could, acted as his own librarian, and made his collection available to (certain) scholars for scrutiny (when he could locate what they were looking for); he also printed his own catalogues and transcriptions, with decidedly mixed success (and at the cost of much bickering with a series of hapless printers). This was an “all-consuming” passion for books, but also a decidedly belligerent one.

It was Munby who traced the course of this extraordinary “career” in collecting, devoting several years to the study of Phillipps’s voluminous papers after they were removed from Thirlestaine House. The result was Phillipps Studies, a landmark achievement in the history of bibliography.2

Phillipps Studies shows how the collection evolved. Progress was continuous but uneven, it seems. A printed catalogue shows that he had, by 1819, accrued a library of 2,894 volumes (including only fifty-four manuscripts). But then there were some dramatic leaps forward. In 1836, for example, he bought up the entire stock of manuscripts from one prominent bookseller, Thomas Thorpe, for £6,000, “on condition that Thorpe did not oppose him at the Heber sale”. (Richard Heber being another extraordinary bibliomaniac, whose library took 216 days to be sold at auction; via one of Thorpe’s competitors, Phillipps purchased 428 of Heber’s manuscripts for a total of £2,500.) Dealers, librarians, fellow collectors: all were to be treated with high-handed hostility.

When Phillipps lived at Middle Hill, a house at Broadway in Worcestershire, sixteen out of the twenty rooms had to be given over by his collection; his wife, Henrietta, and three daughters were confined to the remaining four. The relocation to Thirlestaine House in Cheltenham, over a period of some eight months in 1863, derived from both the practical need for more shelf-space and a characteristic display of blood-mindedness.

Henrietta died in 1832, and he remarried ten years later. “As the companion of his later years”, Alan Bell writes in Phillipps’s ODNB entry, Elizabeth “showed (and needed) great forbearance in the face of his increasing eccentricity.”3 Although Phillipps could, no doubt, have afforded to stay put in Middle Hill and extend the building itself, something else happened in 1842 to increase the need for forbearance: his eldest daughter eloped with James Orchard Halliwell, the precocious Cambridge man whose antiquarian work Phillipps had formerly admired.

Depending on which account you choose to believe (or emphasize), their friendship was terminated by either Halliwell’s lack of a dowry to offer Phillipps’s daughter or allegations that he had stolen manuscripts from Trinity College. It was, in any case, irrevocably broken. And while Phillipps could not stop the scholar-scoundrel Halliwell inheriting Middle Hill, he could leave for Thirlestaine and take his precious collection with him. Moving all of the books and manuscripts took two years to complete. Phillipps was sure, in the meantime, to let his old home fall into as advanced a state of dilapidation as possible.

In that niggardly same spirit (Munby writes),

[Phillipps’s] outbidding of the British Museum and the Bodleian for items which they particularly coveted was much resented. He would never stand down in favour of a public institution, nor would he relinquish any volume which found its way into his clutches. Even when a manuscript, purchased by the British Museum at a sale, was despatched to him by accident, he resolutely refused to restore it to its legal owner.

Efforts were made to see the Phillipps collection of books and manuscripts bestowed on some suitable institution, but they “foundered on the sharp rock of the owner’s personality”, as Munby drily puts it. No deal could be cut that was acceptable to the collection’s irascible owner and Thirlestaine kept it, to be inherited by Phillipps’s youngest daughter, with various conditions about their use, at least until, long after his death, it was finally sold off.4

Sir Thomas Phillipps achieved something unprecedented, but was also (quite rightly, it seems) reviled and ridiculed. In A. N. L. Munby, he found a generous yet clear-sighted biographer and bibliographer, who saw his subject’s follies but also his accomplishments. Thanks to Munby, there is much more of the story to tell; this abridged version of it is, in part, prompted by my remembering visiting Broadway a while ago.

There I found that the small, pleasant museum concentrates on the history of the village for its coaching inns and visiting writers and artists (Lawrence Alma-Tadema, J. M. Barrie). But Phillipps? Not so much. You have to go up Broadway Tower, where he established his printing press, to get a tenuous glimpse of his world.

Middle Hill still stands, I believe, and remains in private hands. Thirlestaine House became part of Cheltenham College almost eighty years ago.

And those books and manuscripts have been scattered to their new homes, never to be reunited again . . .

Most of the facts, figures and quotations in this newsletter come from the useful summary supplied by Munby in a lecture given to the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association in the early 1950s; see Books and the Man (London: W. M. Dawson, 1953), 1–12. I’ve also incorporated a little information from Alan Bell, “Phillipps, Sir Thomas, baronet” in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

A. N. L. Munby, Phillipps Studies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1951–60). Nicolas Barker then supplied a handy abridgement in the form of Portrait of an Obsession: The Life of Sir Thomas Phillipps, the world’s greatest book collector (London: Constable, 1967). Covering everything from Phillipps’s catalogues, family affairs, library formation and library dispersal, Munby only neglected to say much about how the Phillipps books and manuscripts were finally removed to London, in 1946. For an evocative account of this challenging task, see Philip Robinson, “Recollections of Moving a Library: or, How the Phillipps Collection was brought to London”, Book Collector (Winter 1986, vol. 35 no. 4), 431–442.

At Thirlestaine House, Elizabeth sighed, she was “booked out of one wing and ratted out of the other” (quoted by Bell, ODNB).

Besides Halliwell, no Roman Catholic was to set foot in the library. If Phillipps had an obsession besides manuscript-hunting, it was Catholic-hating.

Fascinating..we've driven past Thirlestaine House many times but I never knew its history